Southern Resident Killer Whales

Summary

Neutral

After a steep decline between 1994 and 2001, the population of Southern Resident Killer Whales appears to have stabilized.

Killer whales (or orcas, Orcinus orca) are top predators and cultural icons of the Salish Sea. They're featured prominently in the stories and art of the Coast Salish people, and their presence is important for local tourism. During the spring, summer and fall months, killer whales can be seen regularly in the Salish Sea ecosystem. Orcas have been listed as endangered species in both the U.S. and Canada, and their population is closely tied to the overall health of the ecosystem.

- Learn about the social organization of Southern Resident Killer Whales

Killer whale societies are organized into a series of social units according to maternal genealogy. How much each unit is related to another gets progressively weaker from the smallest social unit (matriline) through the largest (community).

MatrilineMatriline is the smallest orca social unit. Matrilines consist of a group of closely related whales linked by maternal descent. A typical matriline consists of a matriarch (an older female) and her male and female descendents, including granddaughters. In 2010, Southern Resident Killer Whales were organized along 19 matrilines.

PodA pod is a group of related matrilines that share a common maternal ancestor. As pods grow in size over time, they may split into new pods. The 19 matrilines of Southern Resident Killer Whales are found in three pods: J-Pod, K-Pod and L-Pod.

ClanClans are defined by the acoustic behavior of pods. Pods within clans have similar vocal dialects, and pods with very similar dialects are more closely related than those with more different features in their dialects. All Southern Resident Killer Whales belong to J-Clan.

CommunityCommunity is the top level of orca social structure. The community is made up of pods that regularly associate with one another. It is defined by association patterns rather than maternal genealogy or acoustic similarities. Pods from one community have rarely or never been seen to travel with those from another community even though their ranges may partly overlap. There are two resident communities found in the Salish Sea: the northern and southern communities.

What's happening?

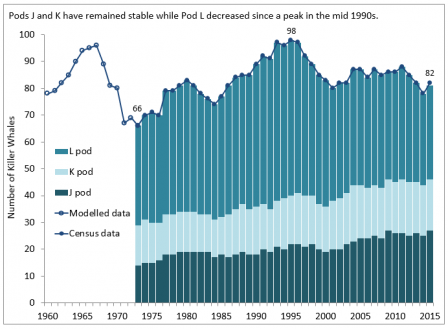

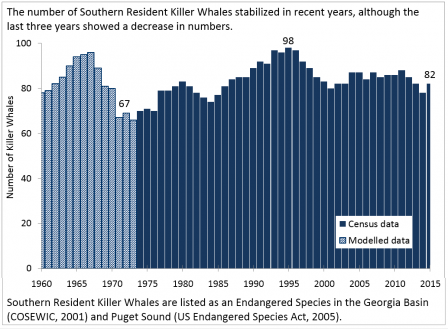

From 1974 to 2015, the resident orca population showed periods of both growth and decline. When we collected our first population census in 1974, 70 whales were sighted. Their population increased by 40% to a high of 98 in 1995, then dropped almost 20% to 80 individuals between 1995 and 2001, prompting governments to list them as endangered species. As of today, the population has just 82 whales, including 4 calves born a year ago, and 2 who were born more recently and who will be officially counted at the end of this year.

Click image for larger version.

Click image for larger version.

- Learn more about what's happening

The three pods within the southern resident orca population have shown different patterns of change. Between 1974 and 2015, J-pod and K–pod grew slightly (25% and 14%, respectively), while L-pod decreased (17%). From their recent peak in 1995 until 2001, L-pod's declining numbers drove the overall decrease in southern resident orca population - prompting the species to be listed as endangered. L-pod has the highest proportion of older females that are no longer reproducing.

Why it's important?

Orcas are culturally, spiritually, and economically important to the Salish Sea. Their population is affected by many environmental factors - such as toxic chemical pollution, bacterial pollution, and sound and physical interference from boats. They rely on healthy populations of salmon, so reductions in killer whale abundance may also provide warnings of reduced populations of salmon.

- Learn more about why it's important

Whale watching and tourism in the Salish Sea provides a significant economic impact. In 1998, the total revenue from whale watching in British Columbia was $69 million. In 2001, Washington residents spent $979 million on wildlife watching, resulting in a total economic output of $1.78 billion and generating or maintaining 22,000 jobs. A large proportion of this wildlife watching occurs in northern Puget Sound which provides many popular whale watching opportunities.

Why is it happening?

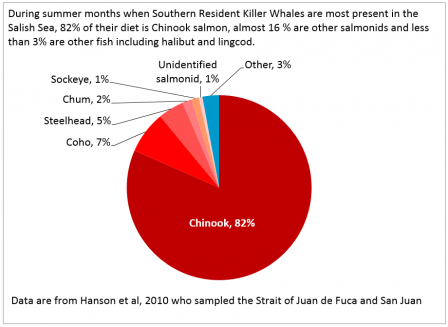

Recent declines in orca population may be linked to threats such as toxic pollution and noise and disturbance from boat traffic. Orcas also rely on healthy populations of salmon - particularly Chinook - which are declining. These factors are all interconnected in a way that suggests an even greater impact on the orca population than can be predicted by studying any one factor by itself. Changing demographics within the small population can further exacerbate these factors and have pronounced influence over social dynamics such as mating, group foraging and social care of calves.

- Learn more about why it's happening

The 30% decline in whales between 1967 and 1971 (see chart under "What's happening?" section) was mostly due to live captures for aquariums all over the world. During this period, Washington and British Columbia served as the primary source of captive killer whales because inland waters offered fewer escape routes, shallower waters made netting easier, and a large network of shore observers provided updates on movements of the whales.

Current threats to recoveryPrey availability – Survival and birth rates in Southern Resident killer whales are correlated with coastwide abundance of salmon and the abundance of their preferred prey, Chinook salmon, has declined from historical levels in the Salish Sea. Fraser River Chinook salmon make up over 80% killer whales’ summer diet when they are in the Salish Sea, and Fraser River stream-type populations are currently of conservation concern as a result of substantial declines over the last decade. Southern Resident killer whales also consume a smaller proportion of other fish and Chinook salmon from the Columbia, Sacramento, Klamath and other coastal river systems outside of the Salish Sea ecosystem.

Learn more about Chinook Salmon » Click image for larger version.

Click image for larger version.Pollution and contaminants – High levels of persistent organic pollutants, particularly bioaccumulating substances such as PCBs which were banned long ago and newer pollutants like those found in flame-retardants (PBDEs), may be preventing the population of Southern resident killer whales from increasing at a rate required for recovery. Southern resident killer whales have been found to carry some of the highest PCB and PBDE concentrations reported in animals. The levels in blubber exceed those known to affect the health of other marine mammals.

Vessels and noise – Cumulative impacts from interactions with vessels and associated noise may interfere with the ability of Southern Resident Killer Whales to communicate and find food. When vessels are present, the whales hunt less and travel more, swim in more erratic paths and increase surface activity with more breaches and tail slaps. They also increase the loudness of their calls when noise levels in their environment are high. The energy cost of these altered behaviors is being studied.

What are we doing about it?

Many agencies are working to address threats to the Southern Resident Orcas by focusing on projects that address reductions in food sources like salmon, pollution, disturbance from boat traffic, and oil spills - all of which can impact the orca populations.

- Learn more about what we're doing

Below are examples of the type of work being done by agencies and non-governmental organizations to help protect orca populations.

- Collaborating to Increase Understanding — The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries is working with Canada's Department of Fisheries and Oceans to evaluate a report by an independent science panel that evaluated effects of salmon fisheries on Southern Resident orcas. They are also working toward understanding other potential factors such as where the whales are in the winter when they are outside of the Salish Sea, demographics, mating patterns and inbreeding effects.

- Collaborating to Inform Management Actions — Port Metro Vancouver is leading the Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program to better understand and manage the impact of shipping activities on at-risk whales throughout the southern coast of British Columbia. Collaborators include Nanaimo Port Authority, Ports of Seattle and Tacoma, Ocean Networks Canada, DFO, Transport Canada, the Vancouver Aquarium and others.

- Whale Watching Guidelines — The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans and U.S. National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration have created voluntary whale watching guidelines to reduce vessel disturbances and manage traffic. The Pacific Whale Watch Association, and organizations such as Straitwatch (for Johnstone Strait and North Vancouver Island) and Soundwatch (for Washington State and Haro Strait) provide outreach for these guidelines and monitor vessel activities in the vicinity of whales. In addition to viewing guidelines, NOAA has implemented regulations to ensure vessels don’t approach whales closer than 200 yards. Visit the Be Whale Wise website Exit for information on guidelines and regulations.

- Improving land leasing activities — The Washington Department of Natural Resource's Aquatic Reserves Program is working to protect aquatic environments from aquatic land leasing activities, with emphasis on protecting habitat and species such as orcas.

- Collaborative Marine Response Plans — NOAA Fisheries has developed an Oil Spill Emergency Response Plan for orcas in partnership with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the SeaDoc Society. In addition, the Canada-United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan provides a framework for Canada-U.S. cooperation in response to marine pollution incidents threatening coastal waters of both countries, and major incidents in one country where the assistance of the neighboring country is required

NOAA Fisheries has developed an Oil Spill Emergency Response Plan for orcas in partnership with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the SeaDoc Society. In addition, the Canada-United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan provides a framework for Canada-U.S. cooperation in response to marine pollution incidents threatening coastal waters of both countries, and major incidents in one country where the assistance of the neighboring country is required.

Five things you can do to help!

- Orcas are sensitive to noise and disturbance from boats. Instead of approaching them in your own vessel, spend a day watching them from a responsibly-managed whale watching vessel. Or watch for them from land with help from the Whale Trail.

- Engage in citizen science by alerting researchers at the Orca Network or the Salish Sea Hydrophone Network when you spot orcas so scientists can track their travel.

- Get involved in efforts to protect and restore salmon habitat in your community. Chinook salmon are especially important to orca populations in the Salish Sea.

- Choose to eat sustainably-harvested salmon and other seafood to help protect wild fish populations.

- Do your part to dispose of unused medicine and chemicals properly. Never dump into household toilets and sinks or outside where they can get into ditches or storm drains. See if your community has a household hazardous waste collection facility that will take your old or unused chemicals.

Related Information

The following links exit the site Exit

- Be Whale Wise

- BC Cetacean Sightings Network

- Center for Whale Research

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Orca Network

- Port Metro Vancouver’s Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation Program (ECHO)

- Salish Sea Hydrophone Network

- The Whale Museum

- The Whale Trail

- Vancouver Aquarium

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans (Canada)

Scientific References

- Alava, J.J., P.S. Ross, F.A.P.C. Gobas. In press, August 20, 2015. Food web bioaccumulation model for resident killer whales from the northeastern Pacific Ocean as a tool for the derivation of PBDE-sediment quality guidelines. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 14 pages.

- Alonso, M.B., A. Azevedo, J.P.M. Torres, P.R. Dorneles, E. Eljarrat, D. Barcelo, J. Lailson-Brito Jr., and O. Malm. 2015. Anthropogenic (PBDE) and naturally-produced (MeO-PBDE) brominated compounds in cetaceans — A review. Science of the Total Environment 481: 619-634.

- Barrett-Lennard, L.G., J.K.B. Ford, K.A. Heise. 1996. The mixed blessing of echolocation: differences in sonar use by fish eating and mammal eating killer whales. Animal Behaviour. 1996(51): 553-565.

- Bigg, M.A., I.B. MacAskie and G.M. Ellis. 1976. Abundance and movements of killer whales off eastern and southern Vancouver Island with comments on management. Arctic Biological Station. Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Quebec.

- Bigg, M.A. 1982. An assessment of Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) stocks off Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Report of the International Whaling Commission. 32: 655-666.

- Bigg, M.A.; Ellis, G.M.; Ford, J.K.B.; Balcomb, K.C. 1987. Killer whales: a study of their identification, genealogy and natural history in British Columbia and Washington State. Nanaimo, B.C.: Phantom Press & Publishers Inc., 1987. ISBN 0920883001.

- Bigg, M. A., P. F. Olesiuk, G. M. Ellis, J. K. B. Ford, and K. C. Balcomb. 1990. Social organizations and genealogy of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 12:383- 405.

- More references

- CANUSPAC, 2003. Canada-United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan. Signed by Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans Coast Guard and US Department of Homeland Security Coast Guard. Washington, DC.

- Constable Associates Consulting, Incorporated and T. Nyman. 2004. Georgia Basin Puget Sound Industrial and Energy Sector Air Emissions Outlook. Prepared for Environment Canada – Pacific and Yukon Region. Vancouver, BC.

- COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) Southern Resident population, Northern Resident population, West Coast Transient population, Offshore population and Northwest Atlantic / Eastern Arctic population in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, ON. Viii + 65pp.

- Cullon, D.L., M.B. Yunker, C. Alleyne, N.J. Dangerfield, S. O’Neill, M.J. Whiticar and P.S. Ross. 2009. Persistent organic pollutants in chinook salmon (Onchorynchus tshawytischa): implications for resident killer whales of British Columbia and adjacent waters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 28(1): 148-161.

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 2008. Recovery Strategy for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Ottawa, ON. Ix + 81 pp.

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 2010. Chinook Salmon Abundance Levels and Survival of Resident Killer Whales. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Pacific Region. Science Advisory Report 2009/075.

- Ford, J.F., G.M. Ellis, and K.C. Balcomb. 2000. Killer Whales, Second Edition: The natural history and genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington. UBC Press, Vancouver and University of Washington Press, Seattle.

- Ford, J.K.B., B.M. Wright, G.M. Ellis and J.R. Candy. 2010. Chinook salmon predation by resident killer whales: seasonal and regional selectivity, stock identify of prey and consumption rates. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2009/101. iv + 43pp.

- Garrett, C. and P.S. Ross. 2010. Recovering resident killer whales: a guide to contaminant sources, mitigation and regulations in British Columbia. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2894. Vancouver, BC.

- Hanson, M.B., R.W. Baird, J.K.B. Ford, J. Hempelmann-Halos, M.M. Van Doornik, J.R. Candy, C.K. Emmons, G.S. Schorr, B. Gisborne, K.L. Ayres, S.K. Wasser, K.C. Balcomb, K. Balcomb-Bartok, J.G. Sneva and M.J. Ford. 2010. Species and stock identification of prey consumed by endangered southern resident killer whales in their summer range. Endangered Species Research. Vol 11: 60-82, 2010.

- Hickie, B.E., P.S. Ross, R.W. Macdonald and J.K.B. Ford. Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) face protracted health risks associated with lifetime exposure to PCBs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007(41): 6613-6619.

- Hilborn, R., S.P. Cox, F.M.D. Gulland, D.G. Hankin, N.T. Hobbs, D.E. Schindler, and A.W. Trites. 2012. The Effects of Salmon Fisheries on Southern Resident Killer Whales: Final Report of the Independent Science Panel. Prepared with the assistance of D.R. Marmorek and A.W. Hall, ESSA Technologies Ltd., Vancouver, B.C. for National Marine Fisheries Service (Seattle. WA) and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Vancouver. BC). xv + 61 pp. + Appendices.

- Krahn, M.M., M.B. Hanson, R.W. Baird, R.H. Boyer, D.G. Burrows, C.K. Emmons, J.K.B. Ford, L.L. Jones, D.P.Noren, P.S. Ross, G.S. Schorr and T.K. Collier. 2007. Persistent organic pollutants and stable isotopes in biopsy samples (2004/2006) from Southern Resident Killer Whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54(2007): 1903-1911.

- Krahn, M.M., M.J. Ford, W.F. Perrin, P.R. Wade, R.P. Angliss, M.B. Hanson, B.L. Taylor, G.M. Ylitalo, M.E. Dahlheim, J.E. Stein and R.S. Waples. 2004. 2004 Status review of southern resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-NMFSC-62, 73 pp.

- Krahn, M.M., P.R. Wade, S.T. Kalinowski, M.E. Dahlheim, B.L. Raylor, M.B. Hanson, G.M. Ylitalo, R.P. Angliss, J.E. Stein and R.S. Waples. 2002. Status review of Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-NMFSC-54, 133 pp.

- Matkin, C.O., E.L. Saulitis, G.M. Ellis, P. Olesiuk and S.D. Rice. 2008. Ongoing population level impacts on killer whales Orcinus orca following the “Exxon Valdez” oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Vol. 356: 269-281.

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency). 2005. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Endangered Status for Southern Resident Killer Whales. Federal Register. 70 FR 69903.

- NOAA. 2006. Endangered and Threatened Species: Designation of Critical Habitat for Southern Resident Killer Whales. Federal Register. 71 FR 69054.

- NOAA. 2008. Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca). National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Regional Office. Seattle, Washington.

- NOAA. 2011a. Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) Five Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Regional Office. Seattle, Washington.

- NOAA. 2014. Southern Resident Killer Whales: 10 Years of Research and Conservation. Northwest Fisheries Science Centre, West Coast Region. . Accessed Sept 23, 2015.

- Parsons, J.M., K.C. Balcomb, J.K.B. Ford and J.W. Durban. 2009. The social dynamics of southern resident killer whales and conservation implications for this endangered population. Animal Behaviour. 2009: 1-9.

- Pacific Salmon Commission. 2015. Annual Report of Catch and Escapement for 2014. Report TCCHINOOK15-2.pdf (PDF) (244 pp, 5.22MB). Joint Chinook Technical Committee Report. Accessed October 6, 2015.

- Rayne, S., M.G. Ikonomou, P.S. Ross, G.E. Ellis and L.G. Barrett-Lennard. 2004. PBDEs, PBBs and PCNs in three communities of free-ranging killer whales (Orcinus orca) from the Northeastern Pacific Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004(38): 4293-4299.

- Ward, E.J., B.X. Semmens, E.E. Holmes and K.C. Balcomb. 2010. Effects of multiple levels of social organization on survival and abundance. Conservation Biology. Volume 25(2): 350-355.

- Wiles, G.J. 2004. Washington State status report for the killer whale. Washington Departmetn of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia. 106 pp.

- Williams, R., D.E. Bain, J.C. Smith and D. Lusseau. 2009. Effects of vessels on behaviour patterns of individual southern resident killer whales Orcinus orca. Endangered Species Research 6(2009): 199-209.