EnviroAtlas Benefit Category: Recreation, Culture, and Aesthetics

Ecosystems provide recreational opportunites and cultural and aesthetic value

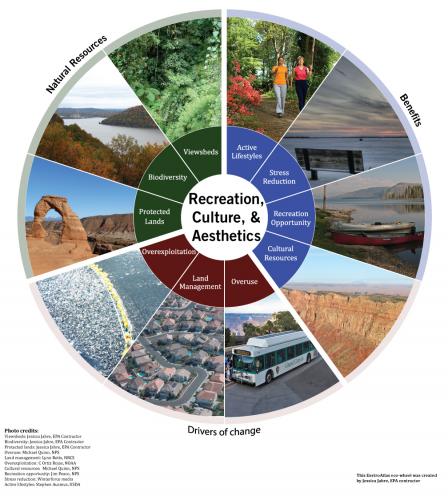

This eco-wheel image shows the natural resources that provide recreational opportunities, the benefits, and drivers of change. People enjoy spending time in outdoor environments such as natural areas, parks, forests, and other green spaces.

This eco-wheel image shows the natural resources that provide recreational opportunities, the benefits, and drivers of change. People enjoy spending time in outdoor environments such as natural areas, parks, forests, and other green spaces.- Each year in the U.S., hundreds of millions of people visit protected lands, such as National Parks, National Forests, National Monuments, National Recreation Areas, National Wildlife Refuges, National Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Historic Sites. In 2012, the National Park system alone had over 282 million recreational visits1.

- Outdoor spaces provide opportunities for recreation, adventure, and physical activity. These spaces are important simply because they are unique places that exist. They are also appreciated for their cultural significance, beauty, educational value, abundance of diverse plants and wildlife, and the sense of place they provide.

- Recreation and tourism associated with outdoor environments can play a huge role in local economies.

- Many groups place high value on historically or culturally important landscapes or on individual species because of their societal significance. Many religions also attach spiritual and religious values to ecosystems or their components2.

Stressors and drivers of change

- There are several human activities that can place stress on the natural areas and local parks where people get recreational and cultural benefits.

- Over-exploitation from extractive uses, such as commercial fishing and game hunting, can remove large numbers of species from marine and terrestrial environments, sometimes reducing their numbers to the brink of extinction3.

- People can also harm natural environments and their inhabitant species through overuse. Outdoor recreation may be a positive, healthful activity for humans, but high numbers of visitors to an area can damage plant life, stress local animal populations, and introduce invasive species

invasive speciesA type of plant, animal, or other organism that does not naturally live in a certain area but has been introduced there, often by people. An invasive species can spread quickly, especially if it has no natural predators in its new home. An invasive species can hurt native species, disrupt ecosystems, and create problems for people (for example, weeds and insects that damage crops).. Many natural landscape features, such as coral reefs, may also be degraded as a result of too much recreational use.

invasive speciesA type of plant, animal, or other organism that does not naturally live in a certain area but has been introduced there, often by people. An invasive species can spread quickly, especially if it has no natural predators in its new home. An invasive species can hurt native species, disrupt ecosystems, and create problems for people (for example, weeds and insects that damage crops).. Many natural landscape features, such as coral reefs, may also be degraded as a result of too much recreational use. - Recreation and tourism often result in increased development, which can compromise ecosystem health.

- Land management and use practices, such as constructing roads to increase access to wilderness areas and building amenities to meet public demand, also affect surrounding ecosystems. Roads contribute to habitat fragmentation, the introduction of invasive species4, and animal deaths as a result of collision5, in addition to detracting from the overall wilderness experience. Competing land uses such as mining or energy development can remove or degrade an area's recreation potential.

- Further development of outdoor recreation areas may also affect the quality of people's interactions with the environment or simply replace the natural areas that people enjoy. For example, although it may be desirable to stay in a house on the edge of a lake, too much development on a lake edge alters the viewshed and can detract from the overall experience.

- Other stressors on recreation and aesthetic experiences include poor air and water quality; haze can reduce visibility in natural areas such as the Grand Canyon6 and poor water quality can reduce aesthetics and potentially preclude some forms of recreation in affected areas. Local urban parks can be affected by over-use, the presence of crime, and the presence of garbage.

Health impacts and benefits

- Various outdoor areas, such as parks, forests, wetlands, and urban green spaces, can have significant cultural value and provide opportunities for people to enjoy nature and recreate in green settings.

- In urban areas, people who live close to green spaces may visit them more frequently. Healthy ecosystems and aesthetically pleasing outdoor environments encourage people to spend more time outdoors, often participating in physical activity.

- Spending time in green environments, especially participating in physical activity while in these environments, can lead to better overall health and wellness by reducing stress and blood pressure, among other benefits.

- Evidence also suggests an increase in self-esteem following green exercise and a greater ability to focus attention. For example, children with ADHD function 10% better after physical activities in green settings, when compared to activities indoors and activities in the built outdoor environment9.

- Although difficult to quantify, feelings of a sense of place and pride in local communities from outdoor green spaces contribute to an area's overall livability.

- Wetlands are important recreation destinations for activities such as birding and have significant historical, scientific, and cultural values7. They also have a wide variety of plant and animal life, which draw people who want to hunt, fish, and recreate in these areas.

- In the U.S., the national forest system receives over 173 million visits per year, where roughly 2/3 of those visits result in people participating in physical activities such as hiking, walking, downhill skiing, fishing or hunting8.

- Usable outdoor areas can also result in economic benefits through the creation of supporting businesses and jobs and increased property values and tax revenue, thus increasing the livability of a neighborhood10.

- For more information on the health benefits of recreating in and engaging with nature, explore the Aesthetics & Engagement with Nature and Recreation & Physical Activity portions of the Eco-Health Relationship Browser.

References

-

National Park Service. 2012. Annual Visitor Report: 2012. Accessed March 2013.

-

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. ExitIsland Press, Washington, DC. Accessed March 2013.

-

Rosser Alison and Mainka, SA. 2002. Overexploitation and Species Extinctions. Conservation Biology, vol 16 (3), p 584 - 6.

-

Mortensen, David A. et al. 2009. Forest Roads Facilitate the Spread of Invasive Plants. Invasive Plant Science and Management. 2(3): 191 - 99.

-

Gunther KA, Biel MJ, Robison HL. 1998. Factors Influencing the Frequency of Road-killed Wildlife in Yellowstone National Park. International Conference on Wildlife Ecology and Transportation, Fort Myers, FL.

-

National Park Service. Grand Canyon National Park View. Accessed March 2013.

-

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1995. America's wetlands: Our vital link between land and water. Office of Water, Office of Wetlands, Oceans and Watersheds. EPA843-K-95-001.

-

Kline JD, RS Rosenberger, EM White. 2011. A national assessment of physical activity in US National Forests. Journal of Forestry 109(6): 343-51.

-

Faber Taylor A, F Kuo, W Sullivan. 2001. Coping with ADD: The surprising connection to green play settings. Environment and Behavior 33(1): 54-77.

-

Fleissner, D., Heinzelmann, F. 1996. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design and Community Policing., in Research in Action. National Institute of Justice.