Historical Radiological Event Monitoring

Since the 1940s, U.S. and foreign nuclear weapons tests, reactor accidents and other radiological events have released radioactive material into the environment. One of EPA's roles during and after these events is to monitor the environment for radiation.

- History of RadNet timeline - shows how the RadNet system has changed over time and some of its important uses.

- Historical Uses of RadNet Data (PDF) (36 pp, 564.16 K, About PDF) - shows historical information about how RadNet data have been used.

On March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of northern Japan. The epicenter of the powerful earthquake was under the Pacific Ocean, approximately 80 miles east of Sendai, where the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is located. The plant’s automatic earthquake detectors successfully inserted all the control rods into the three reactors that were operating at the time. However, less than an hour later, a massive tsunami inundated the Fukushima power plant, causing widespread destruction and knocking out the reactors' emergency cooling systems. The reactors overheated, damaging the nuclear fuel and producing hydrogen explosions that breached the reactor buildings and allowed radioactive elements to escape into the environment.

- How did EPA respond?

EPA’s RadNet system detected nothing unusual in the first week after the Fukushima accident. During this time, EPA deployed additional portable air monitors in Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho and two U.S. Pacific Territories. The RadNet system went on an emergency schedule, with accelerated sampling and analysis of precipitation, drinking water and milk. After a thorough data review showing declining radiation levels in these samples, EPA returned to the routine RadNet sampling and analysis schedule for precipitation, drinking water and milk on May 3, 2011. The last time that EPA detected radioactive elements associated with Fukushima was July 28, 2011 in Hawaii.

On March 18, 2011, the RadNet air monitor in Hawaii detected very low levels of iodine-131 in real-time. Iodine-131 is a radionuclide that would be expected from the Fukushima nuclear incident. During the rest of March and April, laboratory analyses of RadNet samples collected throughout the U.S. detected very low amounts of iodine-131 and other radionuclides expected following a nuclear incident. All of the radionuclides detected in the U.S. from Japan were far below levels of public health concern. No protective actions were needed in the U.S. or its Pacific Territories. After a thorough review of all the sampling and monitoring results showed declining levels of radiation from Japan, RadNet returned to a routine sampling schedule on May 3, 2011.

- Sharing Data with the Public

To keep the public informed, EPA launched a Japan 2011 website which displayed near real-time air monitoring results and associated laboratory analysis data from RadNet. Search the EPA Archives for the EPA Japan 2011 website.

More information and data about EPA's RadNet monitoring of the Fukushima accident can be viewed on the 2011 Japanese Nuclear Incident page

On Saturday, April 26, 1986, a nuclear accident at reactor number four at the former Soviet Union's Chernobyl nuclear power station exploded and burned. The accident, which occurred during unauthorized testing, emitted large quantities of radioactive material. The heat from the fire was so intense that the glowing reactor could be seen even from space, as shown in the satellite photo below.

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station in April of 1986, with red glow of Unit 4 visible near the center.

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station in April of 1986, with red glow of Unit 4 visible near the center.- How did EPA respond?

In the days following the accident, the Soviets released little data on the severity of the accident. Almost no data were available on the extent of radioactive (fallout

falloutRadioactive particles that fall to the ground after a nuclear explosion.) in Europe and the rest of the world. In response to Americans' concern about potential health effects in the United States, the White House assigned the responsibility for leading the U.S. response to EPA. The Agency immediately took several steps:

falloutRadioactive particles that fall to the ground after a nuclear explosion.) in Europe and the rest of the world. In response to Americans' concern about potential health effects in the United States, the White House assigned the responsibility for leading the U.S. response to EPA. The Agency immediately took several steps:- Increased the Environmental Radiation Ambient Monitoring System (abbreviated ERAMS, now RadNet) sampling and analysis frequency.

- Established a group to provide advice on preventing contamination of the food supply and protecting public health.

- Established an information center to gather and distribute facts and data about the accident.

- Arranged daily press conferences to keep the public up-to-date and to give EPA an opportunity to answer the public's concerns.

- How did EPA monitor the plume as it crossed the U.S.?

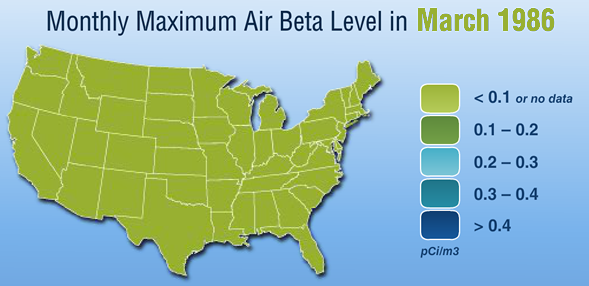

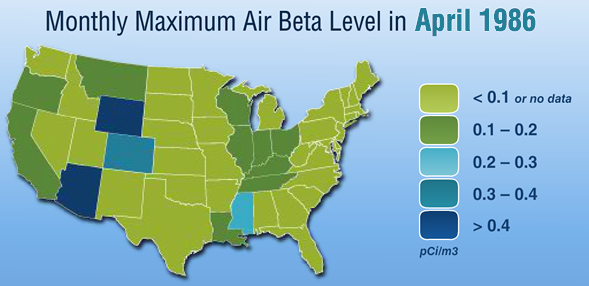

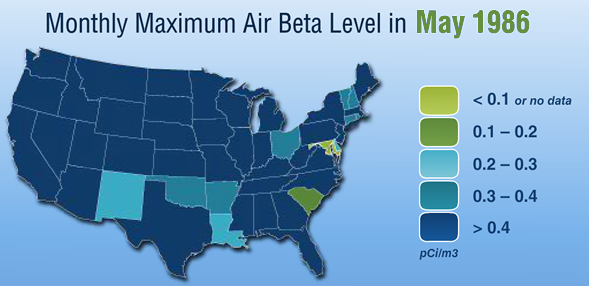

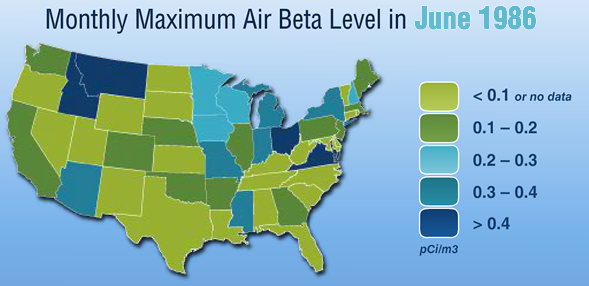

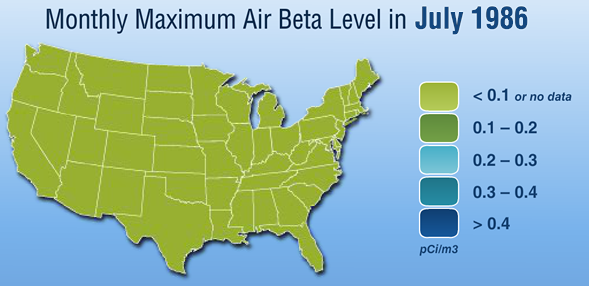

RadNet's predecessor, the Environmental Radiation Ambient Monitoring System (ERAMS), first detected radiation from the accident at ground level on the West Coast one week after the accident. Although radioactivity levels were somewhat elevated, they were well below levels requiring protective actions. The slideshow below shows the fluctuations in air beta levels across the contiguous U.S. between March and July, 1986.

In March 1986, monthly maximum air beta levels across the contiguous U.S. were consistently 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower.

In March 1986, monthly maximum air beta levels across the contiguous U.S. were consistently 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower. In April 1986, several midwestern, southwestern and west coast U.S. states' monthly maximum air beta levels reached 0.3 pCi/m3 or higher.

In April 1986, several midwestern, southwestern and west coast U.S. states' monthly maximum air beta levels reached 0.3 pCi/m3 or higher. In May 1986, nearly all mainland U.S. states had a monthly maximum air beta level of 0.4 pCi/m3 or higher. A handful of states across the nation measured lower levels.

In May 1986, nearly all mainland U.S. states had a monthly maximum air beta level of 0.4 pCi/m3 or higher. A handful of states across the nation measured lower levels. In June 1986, monthly air beta levels remained elevated for some U.S. states, but many states in the contiguous U.S. showed maximum air beta levels of 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower.

In June 1986, monthly air beta levels remained elevated for some U.S. states, but many states in the contiguous U.S. showed maximum air beta levels of 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower. In July 1986, monthly maximum air beta levels across the contiguous U.S. returned to their March 1986 levels of 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower.

In July 1986, monthly maximum air beta levels across the contiguous U.S. returned to their March 1986 levels of 0.1 pCi/m3 or lower.

- How did EPA protect U.S. citizens in Europe?

EPA sent experts to Europe to monitor and assess levels of radioactivity around U.S. embassies. For sometime after the accident, EPA scientists measured radioactivity in the Black Sea and Kiev Reservoir in cooperation with the former Soviet Union.

- Chernobyl Disaster: An Inside Tour

Ten years after the 1986 explosion of Unit 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near Pripyat, Ukraine, EPA staff member Gregg Dempsey was given a rare tour inside the Sarcophagus that surrounds Unit 4. His slideshow from that visit offers a unique historical snapshot of the conditions and challenges inside the plant. It provides views of the interior of Unit 4 not seen elsewhere in Chernobyl photo collections. In addition, it offers the personal perspectives of workers who were present at the time of the accident. One of these workers returns to his flat in the nearby city of Pripyat for the first time since leaving it 10 years earlier.

< Previous | Next > The checkpoint at the entrance of the Chernobyl zone. "ЗОНА ОТЧУЖДЕНИЯ" means "Exclusion Zone."

The checkpoint at the entrance of the Chernobyl zone. "ЗОНА ОТЧУЖДЕНИЯ" means "Exclusion Zone." A view of the many abandoned vehicles in a field used as a contaminated storage yard. Despite 24-hour guards, looters have removed parts from many of the vehicles.

A view of the many abandoned vehicles in a field used as a contaminated storage yard. Despite 24-hour guards, looters have removed parts from many of the vehicles. Soviet helicopters abandoned in the contaminated vehicle storage yard.

Soviet helicopters abandoned in the contaminated vehicle storage yard. At the time of the Chernobyl accident, two newer generation nuclear power plants were under construction by the Soviet Union. They were about 85% complete when the accident occurred. These structures were heavily contaminated and had to be abandoned.

At the time of the Chernobyl accident, two newer generation nuclear power plants were under construction by the Soviet Union. They were about 85% complete when the accident occurred. These structures were heavily contaminated and had to be abandoned. This abandoned building was the main administration building at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

This abandoned building was the main administration building at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Like many public buildings, the administration building at Chernobyl displays the time. Unlike most others, it also displays radiation levels, which at the time of the photo was 81.6 μR/hr (micro Roentgen per hour with micro meaning one millionth). Background radiation levels in most areas are between 6-12 μR/hr.

Like many public buildings, the administration building at Chernobyl displays the time. Unlike most others, it also displays radiation levels, which at the time of the photo was 81.6 μR/hr (micro Roentgen per hour with micro meaning one millionth). Background radiation levels in most areas are between 6-12 μR/hr. The reactor complex extends behind the administration building as Units 1 through 4. The stack at the left of the photo separates Units 3 and 4.

The reactor complex extends behind the administration building as Units 1 through 4. The stack at the left of the photo separates Units 3 and 4. Front view of the "Sarcophagus," a structure built in 1986 to contain most of the radioactive debris from the destroyed Unit 4 reactor.

Front view of the "Sarcophagus," a structure built in 1986 to contain most of the radioactive debris from the destroyed Unit 4 reactor. With Constantin Rudy and "stalker" Artur Korneev, who led the tour inside the Sarcophagus. Stalkers are workers who perform the still dangerous job of surveying the inside of the Sarcophagus for damage and evidence of the causes and progress of the accident. (Notice the heavy canvas, anti-contamination suits.)

With Constantin Rudy and "stalker" Artur Korneev, who led the tour inside the Sarcophagus. Stalkers are workers who perform the still dangerous job of surveying the inside of the Sarcophagus for damage and evidence of the causes and progress of the accident. (Notice the heavy canvas, anti-contamination suits.) Just inside the entrance to Unit 4 is the electronics area. Most of the instruments had been stripped out for use on units that were still operating.

Just inside the entrance to Unit 4 is the electronics area. Most of the instruments had been stripped out for use on units that were still operating. The damaged building at the exterior of the Sarcophagus where the tour begins.

The damaged building at the exterior of the Sarcophagus where the tour begins. In the Unit 4 control room with Constantin Rudy, who had been a control operator in the adjacent Unit 2 at the time of the accident. (Notice the plastic draped over the consoles.)

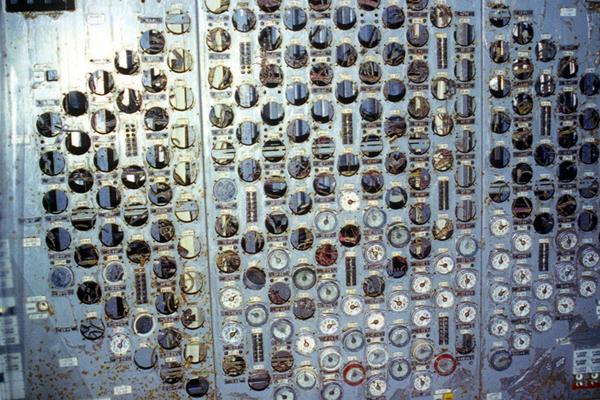

In the Unit 4 control room with Constantin Rudy, who had been a control operator in the adjacent Unit 2 at the time of the accident. (Notice the plastic draped over the consoles.) An annunciator panel in the Control Room, partially stripped for use in the other reactors that remain functional.

An annunciator panel in the Control Room, partially stripped for use in the other reactors that remain functional. Guide Artur Korneev shows radiation dose readings recorded by workers 1 month after the accident, June 16, 1986 — "still 0.5 R/hr" (Roentgens per hour). Background radiation levels in most areas are between 6-12 μR/hr ( 6-12 millionths of a Roentgen per hour).

Guide Artur Korneev shows radiation dose readings recorded by workers 1 month after the accident, June 16, 1986 — "still 0.5 R/hr" (Roentgens per hour). Background radiation levels in most areas are between 6-12 μR/hr ( 6-12 millionths of a Roentgen per hour). A heavy, padlocked door separates the control room from these stairs, which ascend to the main reactor hall.

A heavy, padlocked door separates the control room from these stairs, which ascend to the main reactor hall. In the frantic days immediately following the accident, concrete (such as this approximately two-foot thick layer) was poured indiscriminately in an attempt to control radioactive contamination and reduce worker exposure. This is now viewed as a mistake.

In the frantic days immediately following the accident, concrete (such as this approximately two-foot thick layer) was poured indiscriminately in an attempt to control radioactive contamination and reduce worker exposure. This is now viewed as a mistake. Part way up the stairs leading to the main reactor hall, light shows through an old window, which is partially covered in lead sheeting.

Part way up the stairs leading to the main reactor hall, light shows through an old window, which is partially covered in lead sheeting. The view out the window in the previous photo: the abandoned city of Pripyat is in the distance.

The view out the window in the previous photo: the abandoned city of Pripyat is in the distance. Continuing up the stairs to the main reactor hall: Notice the yellowish covering on portions of the stairs. This is sprayed plastic foam, which was another attempt to cover contamination. But, because loose contamination fell on top of the foam, it proved ineffective.

Continuing up the stairs to the main reactor hall: Notice the yellowish covering on portions of the stairs. This is sprayed plastic foam, which was another attempt to cover contamination. But, because loose contamination fell on top of the foam, it proved ineffective. The way to the reactor hall passes this large debris field directly behind the outside wall of the Sarcophagus. Lights have been laid in the debris field and create an eerie scene.

The way to the reactor hall passes this large debris field directly behind the outside wall of the Sarcophagus. Lights have been laid in the debris field and create an eerie scene. Here the inner support structure of the Sarcophagus is visible. The beams were hastily positioned and welded, because initial rates of exposure were so high that workers could stay in the area only for short periods.

Here the inner support structure of the Sarcophagus is visible. The beams were hastily positioned and welded, because initial rates of exposure were so high that workers could stay in the area only for short periods. Continuing toward the main reactor hall, the walkway passes bags of clay and boron. These were dropped by helicopter in an attempt to stop the fire caused by the explosion.

Continuing toward the main reactor hall, the walkway passes bags of clay and boron. These were dropped by helicopter in an attempt to stop the fire caused by the explosion. The lead sheeting visible in this photo was placed over high radiation areas to minimize the radiation exposure of workers passing along the walkway to the main reactor hall.

The lead sheeting visible in this photo was placed over high radiation areas to minimize the radiation exposure of workers passing along the walkway to the main reactor hall. A viewport for looking into the reactor, damaged by the initial blast and subsequent radiation. The different colors seen in the glass shards were produced by exposure to various levels of radiation.

A viewport for looking into the reactor, damaged by the initial blast and subsequent radiation. The different colors seen in the glass shards were produced by exposure to various levels of radiation. Right: The online refueling machine was launched upwards during the explosion, and landed upside down after crashing through several floors of the Unit 4 building.

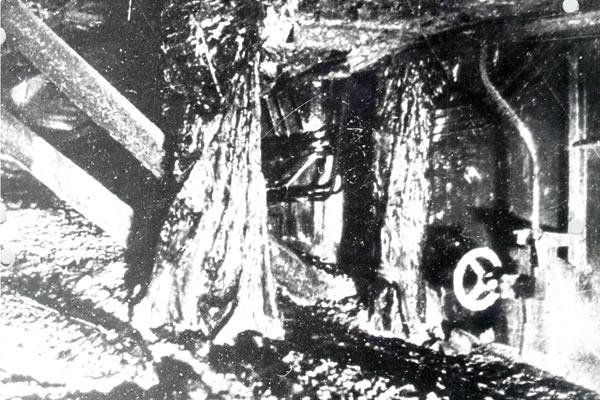

Right: The online refueling machine was launched upwards during the explosion, and landed upside down after crashing through several floors of the Unit 4 building. In the main reactor hall: The top of the reactor, on which the online refueling machine rode, was blown upward and onto its side by the explosion. Melted fuel extends beneath it in the lower part of the photograph.

In the main reactor hall: The top of the reactor, on which the online refueling machine rode, was blown upward and onto its side by the explosion. Melted fuel extends beneath it in the lower part of the photograph. The interior superstructure of Unit 4 showing damage to the concrete from the initial explosion. (Notice the light coming through from the hole in the roof.)

The interior superstructure of Unit 4 showing damage to the concrete from the initial explosion. (Notice the light coming through from the hole in the roof.) In addition to blast damage, water intrusion and temperature differences are causing many parts of the interior concrete to crumble.

In addition to blast damage, water intrusion and temperature differences are causing many parts of the interior concrete to crumble. Exiting the Unit 4 reactor building. What was once the exterior of the building (on the right in the photograph) is now encased by the Sarcophagus.

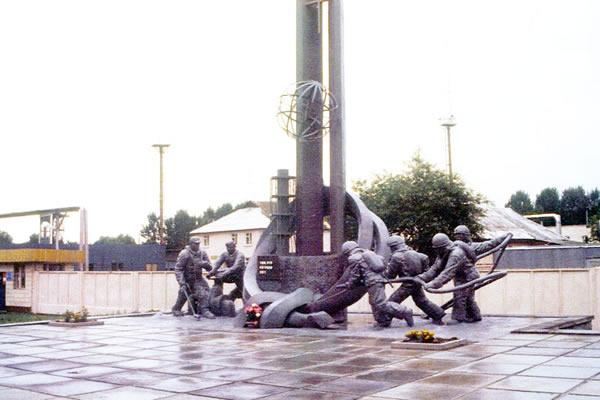

Exiting the Unit 4 reactor building. What was once the exterior of the building (on the right in the photograph) is now encased by the Sarcophagus. Exiting the power plant, the tour passes a monument constructed outside the administration plant to honor the "liquidators" and firefighters who gave their lives during the Chernobyl accident.

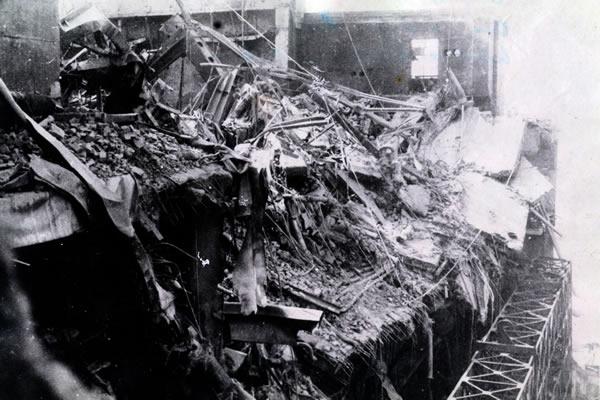

Exiting the power plant, the tour passes a monument constructed outside the administration plant to honor the "liquidators" and firefighters who gave their lives during the Chernobyl accident. A Ukrainian photograph showing and extensive blast-damage rubble-field before the Sarcophagus was built.

A Ukrainian photograph showing and extensive blast-damage rubble-field before the Sarcophagus was built. A Ukrainian aerial photograph of the top of the reactor taken shortly after the accident and before the construction of the Sarcophagus. It illustrates the massive damage to the structure that contained the reactor.

A Ukrainian aerial photograph of the top of the reactor taken shortly after the accident and before the construction of the Sarcophagus. It illustrates the massive damage to the structure that contained the reactor. Ukrainian aerial photograph of Unit 4 shortly after the blast. The deepest hole (see arrow) is where the reactor was.

Ukrainian aerial photograph of Unit 4 shortly after the blast. The deepest hole (see arrow) is where the reactor was. Ukrainian photo of the construction of the Sarcophagus. The large trucks in the foreground provide a sense of scale. (Note the damaged structure at the top of the photo.)

Ukrainian photo of the construction of the Sarcophagus. The large trucks in the foreground provide a sense of scale. (Note the damaged structure at the top of the photo.) Melted and resolidified fuel that had flowed into the lower reactor area, below the main reactor room.

Melted and resolidified fuel that had flowed into the lower reactor area, below the main reactor room. Melted fuel flowed through this pipe and resolidified.

Melted fuel flowed through this pipe and resolidified. Pine trees growing near the Sarcophagus are under severe radiation-induced stress.

Pine trees growing near the Sarcophagus are under severe radiation-induced stress. Radiation stress has caused changes in tree growth patterns, such as this formation of "witch's broom," a condition in which too many shoots form on a bough.

Radiation stress has caused changes in tree growth patterns, such as this formation of "witch's broom," a condition in which too many shoots form on a bough. Loss of orientation, a condition in which branches no longer grow toward the sun, is another change induced by stress from radiation exposure.

Loss of orientation, a condition in which branches no longer grow toward the sun, is another change induced by stress from radiation exposure. Moss growing in Pripyat is contaminated with cesium137 and strontium90. Visitors are warned not to touch or step on it.

Moss growing in Pripyat is contaminated with cesium137 and strontium90. Visitors are warned not to touch or step on it. Dairies are quite common in this area of Ukraine. This one, even in 1996, was back in operation.

Dairies are quite common in this area of Ukraine. This one, even in 1996, was back in operation. Partisan's Tree, a famous Ukrainian symbol. During WWII, the Nazis hanged resistance fighters from this tree. It died due to radiation stress. (Note the proximity of the Chernobyl plant shown in the background.)

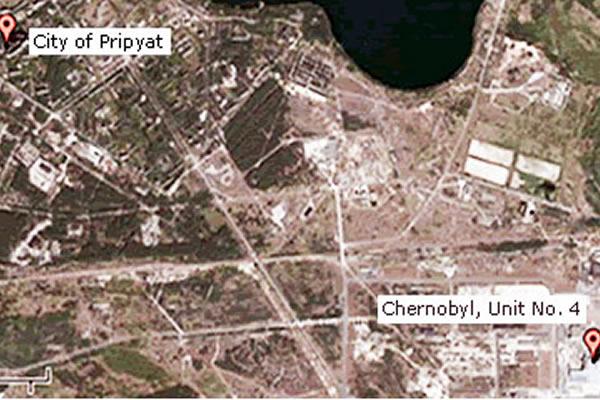

Partisan's Tree, a famous Ukrainian symbol. During WWII, the Nazis hanged resistance fighters from this tree. It died due to radiation stress. (Note the proximity of the Chernobyl plant shown in the background.) The City of Pripyat, Ukraine is approximately 2 Km from the Chernobyl Nuclear Reactor. (Image courtesy of Tagzania, powered by Google Maps.)

The City of Pripyat, Ukraine is approximately 2 Km from the Chernobyl Nuclear Reactor. (Image courtesy of Tagzania, powered by Google Maps.) This is a photograph of the gated entrance to the abandoned nearby city of Pripyat. Constantin Rudy, shown in earlier photographs, and other workers at the Chernobyl plant were the residents of Pripyat before the accident. The area remains closed to prevent looting.

This is a photograph of the gated entrance to the abandoned nearby city of Pripyat. Constantin Rudy, shown in earlier photographs, and other workers at the Chernobyl plant were the residents of Pripyat before the accident. The area remains closed to prevent looting. Two newer apartment buildings ("flats") abandoned in Pripyat.

Two newer apartment buildings ("flats") abandoned in Pripyat. One of the abandoned city administration buildings. (Note the Ferris wheel in the background.)

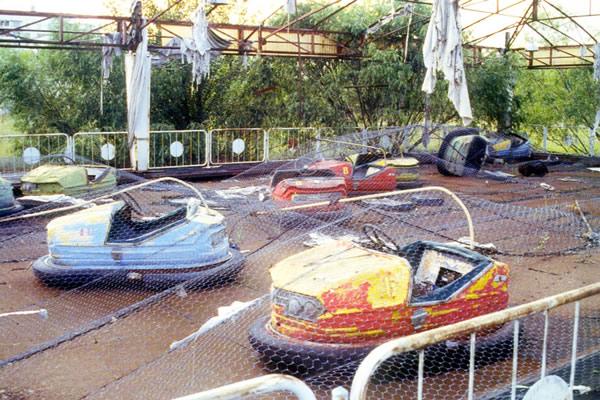

One of the abandoned city administration buildings. (Note the Ferris wheel in the background.) At the time of the accident, the fair was in town for May Day celebrations. These rides, set up in the town plaza for the celebration which never occurred, are now abandoned.

At the time of the accident, the fair was in town for May Day celebrations. These rides, set up in the town plaza for the celebration which never occurred, are now abandoned. After one of the cars was stolen, the bumper car ride was covered with wire mesh to prevent further looting.

After one of the cars was stolen, the bumper car ride was covered with wire mesh to prevent further looting. This soccer field was under construction at the time of the accident and is now overgrown and barely recognizable.

This soccer field was under construction at the time of the accident and is now overgrown and barely recognizable. Constantin Rudy standing in front of the apartment building in which he and his family lived before the accident.

Constantin Rudy standing in front of the apartment building in which he and his family lived before the accident. The stucco on the exterior of the building is contaminated with radioactive fallout from the explosion.

The stucco on the exterior of the building is contaminated with radioactive fallout from the explosion. Constantin returns to his apartment for the first time since being forced to abandon it in 1986.

Constantin returns to his apartment for the first time since being forced to abandon it in 1986. Inside the apartment's entryway: Soldiers had removed most personal property years earlier to prevent looting.

Inside the apartment's entryway: Soldiers had removed most personal property years earlier to prevent looting. Constantin's young daughter occupied this room.

Constantin's young daughter occupied this room. As illustrated by this room's ceiling and walls, any buildings are showing significant damage from water intrusion and seasonal temperature variations.

As illustrated by this room's ceiling and walls, any buildings are showing significant damage from water intrusion and seasonal temperature variations. Leaving Pripyat along its main road, which now, like the rest of the city, is abandoned and overgrown.

Leaving Pripyat along its main road, which now, like the rest of the city, is abandoned and overgrown.Constantin Rudy died on February 8, 2006. This presentation is dedicated to him and to all the victims of the Chernobyl accident.

This concludes the presentation.

- Resources

- Backgrounder on Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

This page describes the accident and provides links to reports on its aftermath. - Researchers Determine Chernobyl Liquidators' Exposure

Lawrence Livermore Laboratory

This article describes how researchers use special techniques to monitor genetic damage in people exposed to ionizing radiation. - Maps and additional photographs of Pripyat, Ukraine and Chernobyl Exit

Tagzania

This site provides an interactive map with links to pictures.

- Backgrounder on Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident

On September 30, 1999, three workers at the Japan Nuclear Fuel Conversion Company transferred several times the allowable limit of enriched uranium into a precipitation tank, bypassing criticality controls. The transfer caused an uncontrolled, self-sustained nuclear reaction. Though the accident released radioactive noble gases and gaseous radioiodine, most of these substances were confined to the building.

EPA used the Environmental Radiation Ambient Monitoring System (ERAMS), now RadNet, to monitor the radioactivity in air, precipitation and pasteurized milk. As expected, no increase in radioactivity above typical background levels was measured in any of the samples analyzed, so protective actions were not needed.

The People’s Republic of China conducted two test detonations of nuclear weapons on September 26 and November 17, 1976. Both detonations were conducted above ground, injecting radioactive material into the atmosphere.

EPA used the Environmental Radiation Ambient Monitoring System (ERAMS), now RadNet, to monitor the radioactivity in air, precipitation and pasteurized milk. EPA’s monitoring system identified low, but measurable, quantities of radioactive material throughout the United States from the September 26 test. No additional material from the November 17 test was detected. As a result of the findings, state agencies in Connecticut and Massachusetts ordered farmers to switch dairy herds to stored feed only, minimizing the potential impact on milk supplies. EPA continued to monitor radioactivity levels until they returned to normal background levels in November 1976.

ERAMS monitored each atmospheric nuclear test, as the system is continuously in operation. EPA also responded to the last recorded atmospheric test on October 16, 1980 (which occurred in China) with increased milk collection.