Promote Green Government Operations

Local governments have an opportunity to achieve substantial cost savings, demonstrate energy and environmental leadership, develop local municipal capacity and expertise, and raise public awareness by promoting green government operations. “Green” government operations are operations that minimize an entity’s environmental impact, including its energy use, water use, waste and pollution generation, and greenhouse gas emissions. While municipalities and counties across the country face tight budgets, smart investments can reduce operational costs and demonstrate how to implement climate-friendly, green activities.

These guidelines below provide local governments with information on how to make their operations greener and then use those examples to inspire and promote community action. Promoting green government operations might include:

- Increasing energy efficiency (e.g., conducting an energy audit and efficiency upgrades at city hall, building city facilities to Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) standards, installing a revolving door in high traffic entrances).

- Using alternative energy (e.g., using solar panels to power electronic parking meters, installing a wind turbine to power government buildings).

- Reducing waste (e.g., replacing single-use water bottles with pitchers and reusable glasses at meetings, introducing composting receptacles in staff kitchens, replacing individual trash bins with desk-side recycling bins).

- Encouraging greener transportation choices (e.g., providing bike racks, showers, and locker rooms for city employees who ride to work; incentivizing staff use of public transportation or carpools; purchasing electric or hybrid vehicles for the city fleet).

- Implementing sustainable land use decisions (e.g., locating public services near transit options, limiting the number of parking spots required for public buildings).

- Increasing the resilience of government assets and reducing the heat island effect through government infrastructure (e.g., installing green infrastructure at government facilities, such as green and cool roofs, rain gardens, cool and permeable pavements; paving roads with resilient materials).

The following key steps describe how to effectively design and implement green upgrades, with a focus on government facilities. Steps include convening decision-makers, understanding existing efforts, and publicizing stories that demonstrate success. Information on adopting a policy in the form of a plan, ordinance, regulation, or other mechanism to mandate sustainable actions is covered under Adopt a Policy. Programs related to incentivizing or otherwise encouraging behavior changes in the community are covered under Engage the Community.

To be connected with a local representative with experience implementing these types of programs, contact us.

Key Steps

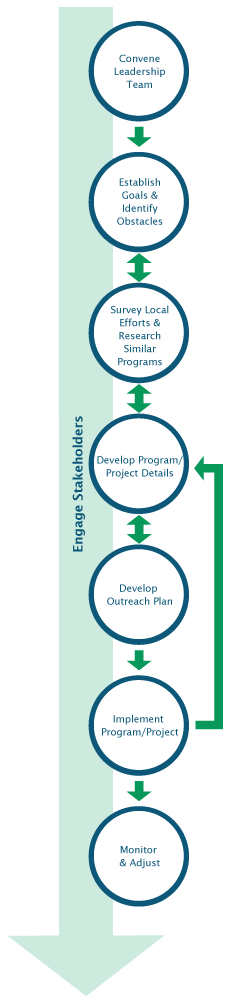

Here we discuss the key steps in designing and implementing green government upgrades. The steps in this process are not necessarily intended to be pursued in linear order, as illustrated in the diagram. For example, establishing goals and identifying obstacles, surveying local efforts and researching similar programs, developing program/project details, and developing an outreach plan may all happen simultaneously. Alternatively, earlier steps may be revisited after subsequent steps are explored. In addition, engaging stakeholders occurs throughout all steps of the process and is integrated into each of the step descriptions.

- Step 1: Convene Leadership Team

Once your government has decided to make its operations greener, identify the key people or partners who can help articulate objectives and ensure that goals are realized over the course of the project. This may include a combination of individuals such as inspired staff members, leaders in the community, an existing green team, specific departments within the government, a facility that has identified an opportunity to make a change, or private entities. Gather a leadership team and designate roles and responsibilities.

Depending on the effort, the leadership team may range in size from a few people within your entity to a larger advisory committee that includes people from your department, other local government agencies, and relevant stakeholders. In determining the appropriate team, consider the various attributes and strengths of potential stakeholders. Consider individuals who offer valuable input, important buy-in, enthusiastic support, leadership, and unique experiences or perspectives.

Visit the Reach Out & Communicate phase for specific guidance on how to reach out to potential project partners.

Case in Point:

Case in Point:In 2010, the Town of Preble, New York, (population ~1,300) was awarded a grant to conduct an energy efficiency upgrade for the town hall. The grant was one of seven competitive $30,000 matching sub-grants awarded to municipalities to address climate change by the Central New York Regional Planning and Development Board (CNY RPDB) through an EPA Climate Showcase Communities grant.

While preparing the grant application, Town Supervisor James Doring and Town Board Member Debra Brock recruited participants to sit on an advisory committee responsible for project implementation. Doring and Brock successfully recruited a representative from the local department of public works, the town judge, and a resident who worked for a facilities department at a local state college and was familiar with the heating systems. This dedicated group of local decision-makers and experts worked closely with the CNY RPDB staff to find viable solutions for the town. Preble’s leaders found that it was essential to identify a group of trusted local project stewards because the project was introducing the community to new and unfamiliar technology. Without the foundation of a trusted advisory committee, it is likely that this project would have ended prior to completion.

- Step 2: Establish Goals and Identify Obstacles

Before initiating a project, define an explicit purpose for the program. Is your entity trying to decrease operational costs, reduce government emissions, or provide an example that citizens or businesses can adopt? Do you have a specific goal, such as GHG reduction, waste diversion, or urban heat island reduction? The goals can help serve as a guide or focal point throughout the project. Be explicit about what your government is trying to accomplish through the project.

Keep in mind that promoting green government operations can include two distinct components: implementing the project itself (e.g., installing a capital project, changing government operations), and showcasing the project to the public or another sector as an example. Accordingly, develop specific, quantifiable goals for both internal outcomes (e.g., energy use reduction) and external outcomes (e.g., the number of businesses that learn about the program). Visit the Set Goals & Select Actions phase for more detailed guidance on articulating specific goals.

Once goals are articulated, identify any known obstacles (e.g., regulatory, financial, knowledge, or political) that might impede success.

Helpful Tip:

Helpful Tip:As you conceptualize your project, consider the amount and types of available and potential resources, including funding and staff time. Visit the Obtain Resources phase for thorough guidance on how to obtain necessary resources. If the project is the result of available funding, make sure that the project objectives and scope fit within the budget and any restrictions. If you will have to identify additional resources for this project, be realistic about what can be accomplished with attainable funds and time.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: The opportunity for Preble, New York, to receive technical support from CNY RPDB inspired the town to pursue a project to promote green government operations. Preble was interested in financial savings and starting a sustainability project, but did not know where to start.

Through the Climate Showcase Communities grant program, Preble and CNY RPDB evaluated the town needs and identified two potential projects: (1) replacing the Department of Public Works’ garage, and (2) conducting an energy efficiency retrofit for the town hall. An initial assessment revealed that updating the town hall, which had been built in 1906, would provide immediate benefits, including financial savings and relief from drafty windows and noisy in-wall air conditioning units. The retrofit also provided an opportunity to replace the antiquated fuel oil heating system with a high-efficiency heat pump system, which had the added bonus of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Preble took advantage of a program supported by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) that offers small commercial and home energy assessments to have a local HVAC contractor perform a “blower door test” to identify air leaks. This assessment revealed that the building had an air exchange that was 12 times higher than it should have been for a building that size. This helped define the explicit need for an energy efficiency upgrade that included air sealing and insulation.

- Step 3: Survey Local Efforts and Research Similar Programs

Prior to implementing a new initiative, survey ongoing efforts both internally, for complimentary or competing projects within your entity, and externally, for other entities that may be implementing similar projects.

Understand Local Efforts

Survey what is already happening locally related to your goals. For example, is there a non-profit that is promoting a similar project? Are there departments that have already implemented projects within their operations that could be expanded across the government?Look for efforts that target the same audience or address a similar topic. Consider whether you could combine your efforts or otherwise collaborate with existing programs. Set up meetings and ask the people who led those initiatives what considerations and obstacles they had to overcome and how they achieved success. Explore opportunities to build off of existing networks and programs.

Learn from Others

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. Learn from other communities that have taken on similar initiatives. EPA's Climate Showcase Communities have implemented a wide range of projects and EPA’s Urban Heat Island Community Actions Database includes examples of projects to reduce the heat island effect; visit the respective project pages for inspiration. Reach out to your counterparts at other entities and ask about best practices and lessons learned. Inquire about the components of their programs that worked well and any advice they have for your initiative. Use students at local universities. Seek opportunities to incorporate a project to promote green government operations into the curriculum of an applied course. Helpful Tip:

Helpful Tip:Although it is valuable to learn from others, make sure that your project is locally applicable. For example, a campaign to increase government employee use of public transportation may not be feasible in a small town that has limited bus service. A plan to coordinate carpools and add bike racks in front of city hall may be a more effective way to decrease single-occupancy vehicle trips to work.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Heating technology had greatly advanced since the fuel oil system was installed during a 1970s renovation of the Preble, New York, town hall. CNY RPDB encouraged the town to consider comprehensive solutions using new technologies, such as a heat pump system that would address heating and cooling issues together. However, the town was not familiar with alternative heating options and the viability of renewable energy systems like solar panels. In particular, decision-makers were not confident that a heat pump system would be sufficient for severely cold days.

Through work with CNY RPDB and a local contractor who participates in the NYSERDA ENERGY STAR® certification programExit, project leaders learned about heating options that proved to be more sustainable and cost-efficient than heating oil. This included conversations with experts to answer questions about the viability of solar energy systems in upstate New York and a tour of a ski resort that had successfully installed a heat pump system.

Through this research, Preble was able to consider new ideas and integrate solar panels to amplify the financial and GHG reduction benefits of the project. CNY RPDB and the contractor provided the committee with options that included the integration of renewable energy. A detailed evaluation of the options revealed an anticipated return on investment in a little more than 6.5 years. This made the large initial investment much more attractive. After one year of operation, an updated evaluation lowered the estimated return on investment to 5.8 years.

- Step 4: Develop Program/Project Details

Once you have convened a leadership team, defined your goals, and conducted research on existing efforts, it is time to identify specific activities and actions that best suit the needs of your community. You may find that you can simply replicate or expand an existing program. Alternatively, you might synthesize a combination of successful elements from various programs or develop an entirely new project.

As you flesh out the details of your effort, keep the following elements in mind:

- Scope: Define the scope of the project and explicit milestones for implementation. Consider whether a phased implementation or pilot project is appropriate given the available resources and capacity of the leadership team.

- Location: Select the project site, if applicable, and justify the selection.

- Implementers: Hold conversations with key stakeholders, including “implementers,” to identify and address concerns early. For example, if the project involves changes in building operations or custodial practices, engage the facilities manager and/or head custodian to make sure that the project can be implemented as it is designed. See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information about engaging stakeholders.

- Audience: Identify who will be affected by the project, including any stakeholders that must change their behavior for the program to succeed. Seek to understand the motivations of these stakeholders and engage them appropriately. In addition, identify who should know about the efforts and successes of the project. Consider whether the entity reports up to a county or state government. Is the ultimate audience the taxpayers? Is the audience made up of citizens and business owners? See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information about engaging stakeholders.

- Synergy: Make sure that the project fits into and complements other community plans. For example, does this project support an existing transportation or stormwater initiative? How can this new effort further the effectiveness or complement existing projects?

- Legal considerations: Comply with all applicable local, state, and federal laws, getting permissions where needed. Seek approvals, as necessary.

- Resources: Define and secure needed resources (see the Obtain Resources phase). Will sufficient resources be available for the full project duration, including maintenance requirements and ongoing implementation?

- Tracking and reporting: Develop a plan to measure, report, and evaluate quantifiable metrics. Use guidance from the Track & Report phase to identify the appropriate metrics.

Helpful Tip:

Helpful Tip:Engage stakeholders early and often.

Most projects that promote green government operations require some behavior or maintenance change. You can increase the potential for project success by listening and responding to the needs and concerns of the people who will be responsible for ongoing implementation. Remember to keep conversations focused on implementation; use these conversations to move the project towards reaching the outlined goals. For example, if your entity would like to start using biodiesel vehicles, talk with the people who maintain, fuel, and drive the vehicles to address potential obstacles before they detract from project success. Visit the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information on engaging stakeholders.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Scope: The energy efficiency project to upgrade the Preble, New York, town hall included a blower door test, air sealing and insulation, installation of an air-source heat pump system, installation of vinyl windows, upgrading to an efficient lighting system, and installation of solar panels on the roof. All of the elements of the project were sized to work together and integrated into one program that resulted in dramatic increases in efficiency and comfort in the town hall.

Location: The town hall is one of two government-operated public buildings in Preble, New York, and the team determined that this would be the most effective use of the sub-grant from CNY RPDB.

Implementers: The project team worked with CNY RPDB staff and a local engineer to identify the appropriate scope and bid documents. The heating/cooling system and the solar panels require little to no maintenance and both are covered by 2-year warranties on hardware and installation.

Audience: As a pilot project, the ultimate audience was the general public and neighboring towns, who could be inspired by the project to implement similar upgrades. Stakeholders were engaged through public meetings.

Synergy: This project was part of a larger community effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As part of their participation with CNY RPDB, Preble developed a greenhouse gas inventory and completed a sustainability action plan.

Legal considerations: Due to the age of the building, the project team had to confirm that it was not designated a historic building and that the solar panels and window upgrades would not violate any historic designations. Since the building was not designated historic, there were no such restrictions. However, the building does have historic community value and the project team decided to locate the solar installation on the back side of the building to limit the aesthetic impact of the project.

Resources: Preble was able to piece together financial assistance from several sources. With the $30,000 Climate Showcase Communities grant, the town was able to leverage additional funding, take advantage of incentive programs, and justify a reallocation of town resources that had been collected for another project. The 6.5 year return on investment also helped convince decision-makers that this was a wise investment. The total cost of the project was approximately $136,000 and the town was able to secure assistance for more than half of the cost.

Very early in the project, it seemed that the financial hurdles would prevent the project from moving forward. Preble worked with CNY RPDB to evaluate the long-term value of the project and decided to increase the town’s spending from $30,000 to $49,000. As a result, the city was able to leverage enough funding from multiple sources to make the project a reality.

Tracking and reporting: The project had two major areas of performance that could be measured: energy produced by the solar panels and energy used by the building. Although the town did not set up a specific tracking system, these metrics are readily available and the town is able to track the success of the project through these measurements.

- Step 5: Develop Outreach Plan

If one of your project goals is to inspire citizens and businesses, develop an outreach plan to publicize your efforts and successes. Even if the project is not focused on inspiring others, you may want to develop an outreach plan to assure taxpayers that the project is beneficial. An outreach plan will likely include some variation of the following steps.

- Identify a spokesperson: Select an individual or group to be the face of the project. For example, would the mayor or municipal manager be appropriate for making announcements about the project? Would it be helpful to have a joint announcement from multiple city council members? Engage community leaders, elected officials, and community champions to raise the visibility of the project, as appropriate.

- Select an approach: Identify the best method or combination of methods to spread the word about the project. Consider traditional media (e.g., local newspaper), social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, blogs), local networks and leaders, and local events. Consider how announcements are typically made in your community and how different stakeholders receive information. For an example of effective use of social media, visit the Central New York Energy Challenge Facebook pageExit.

- Identify what you will report: Select the metrics you will report publicly. For example, consider tracking energy, dollars, and carbon dioxide emissions saved through a city hall retrofit. See the Track & Report phase for more information on reporting metrics. Consider communicating reductions in relatable terms like the “number of mature trees preserved” or another tangible measurement. Use EPA’s GHG Equivalencies Calculator to translate abstract emissions amounts into more meaningful measurements.

- Develop a reporting schedule: Determine how often to publicize metrics. Will you post monthly updates on financial and resource savings? Is an annual or bi-annual report sufficient?

- Set goals: Establish outreach goals and metrics that are separate from the goals and metrics for the government operations project itself.

See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information on communicating with stakeholders and the public.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Preble, New York, held town board meetings and public presentations to share information about the project. Once the local contractor conducted the blower door test and research revealed the potential cost savings that could result from retrofitting the heating system, the leadership team used this information to gain project support. The town wanted to see a project that could be justified financially and that would improve conditions in their community building, which was expensive, cold, and uncomfortable in the winter.

The project also gained interest from neighboring jurisdictions. In addition to providing residents with a local example of the value of air sealing and insulation, the project demonstrated that heat pumps and solar energy production are both viable in upstate New York. Pedestrians have seen the solar panels, which have caught the attention of curious residents.

As a result of this project, the board member on the leadership team became an outspoken champion of the project and installed a 9-kW solar system on her own house. Although a formal outreach strategy was not explicitly developed, the results of the project were highly visible and tangible—people in the town who use the building can actually feel the difference the improvement has made, since the building is no longer as loud or drafty. In addition, a Preble Town Hall PV System Profile is publicly available onlineExit.

- Step 6: Implement Program/Project

Identify a project manager to oversee implementation. Select a project manager who has both the capacity and the interest to achieve project success. Follow the entity’s policies and procedures. As explored in Step 4, consider implementing an incremental rollout or starting with a pilot project. Implementation will likely require some variation of the following steps.

- Acquire materials. Comply with your entity’s procurement policies/procedures to acquire needed materials (e.g., new windows or light bulbs, recycling bins, reusable materials). Develop a request for proposals (RFP) and select a vendor from competitive bids, if necessary.

- Engage staff. If the entity has the capacity to do the work in-house, identify the staff and resources necessary to complete the project. Alternatively, consider contractors or volunteers.

- Conduct the project. Install infrastructure, roll out incentive programs, adjust operational protocols, or complete other necessary steps for actual project implementation.

- Track progress. Visit the Track & Report phase for information on understanding project progress and success.

- Communicate successes. Follow the steps of the outreach plan outlined in Step 5, if appropriate.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: The energy efficiency upgrade at the Preble, New York, town hall took nearly two years to implement. Several hurdles extended the duration of the project:

- Prior to this project, Preble had performed a commercial building energy assessment. However, due to the building’s size and type of construction, it was determined that a residential assessment was more appropriate because it also considered insulation needs. This proved to be a critical decision in the success of the project given the need for insulation.

- Public projects require consensus among local government departments and the public.

- The heat pump and solar panels were innovative solutions that had not been tested in Preble. Additional research and efforts were required to reach agreement between decision-makers and the public.

- Several sources of funding had to be acquired to finance the project.

September 2013 marked the first full year of operation since the project was completed.

One lesson that Preble learned was how to evaluate solar panel bids. For most municipal contracts, the “lowest qualified bid” is selected. However, Preble decided to take a more comprehensive approach to assess the bids. The evaluation criteria considered the size of the panels, manufacturing location, and the qualifications of the installer.

- Step 7: Monitor and Adjust

Track the metrics identified in Steps 4 and 5 over the course of the project to measure progress and make adjustments as needed. Facilitate ongoing conversations with stakeholders to receive feedback. Collect and analyze outcome data and communicate results and lessons learned to the community.

Visit the Track & Report phase for more information on how to develop an effective process to collect and analyze data, and report on project outcomes.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Preble, New York, conducted an assessment of the building’s history to measure the impact of the energy efficiency upgrades to the town hall. The town is measuring both energy consumption and energy generation.

Energy consumption is measured by the amount of energy (in kilowatt hours) used and the associated cost. The projected annual savings from the project was approximately $8,000. At the end of the first year of operations, the energy efficiency improvements outperformed the projected savings.

Energy generation is measured by the inverter system that converts solar energy into usable electricity. The company that runs the system runs a data center and posts real-time information online for each of the inverters on its network. At the town hall, the projected annual production was about $1,200 in electricity. At the end of the first year of operations, energy production was slightly lower than the projection. This was attributed to a particularly rainy June in upstate New York, which is believed to have reduced the amount of energy generated by the solar panels.

Energy generation is measured by the inverter system that converts solar energy into usable electricity. The company that manufactures the inverter posts real-time energy production information online which is made available to the public through the Town of Preble website. On average, the town hall PV system has been providing nearly 50% of their total annual use. By tracking monthly averages for both consumption and generation, Preble is able to assess both the overall impact of the system and more detailed trends. For instance, if a system fails one month, February is unusually cold, or June is particularly cloudy; it is possible to account for those anomalies.

Case Studies

Portland, Oregon: Sustainability City Government PartnershipExit

A collaborative effort to integrate sustainable practices and resource efficiency into municipal operations.

Arlington County, Virginia: Energy Efficiency in Local Government Facilities and Operations

Arlington County’s Fresh AIRE (Arlington Initiative to Reduce Emissions) Program launched to improve the energy efficiency of county buildings and operations (highlighted on page 47 of document).

King County, Washington: Energy-Efficient Product Procurement

An environmental purchasing program that started as an initiative to promote recycled materials and is now a comprehensive purchasing program with several energy-related and environmental goals.

Phoenix, Arizona: Energy Conservation Program

An energy conservation program that has evolved into a broader sustainability program that involves land use, recycling, transportation, and water conservation in addition to energy efficiency (highlighted on page 47 of document).

Los Angeles, California: Good Practices in City Energy Efficiency (11 pp, 243 K, About PDF) Exit

A project to replace 140,000 inefficient street lights with energy-efficient alternatives.

Tools and Templates

Alameda County, California: Model Civic Green Building OrdinanceExit

StopWaste.org, which provides model policies, ordinances, and contract specifications for county residents, businesses, and local governments.

EPA’s Energy Efficiency in Government Operations and Facilities

Resources and tools on building energy efficiency, including relevant ENGERY STAR® publications.

Delaware Valley Regional Planning CommissionExit

Program website that includes a suite of tools that local governments can use to promote green operations, including a baseline analysis tool, a regional GHG inventory tool, and an electric vehicle ownership tool.

New York State Climate Smart CommunitiesExit

A collection of resources that provides an overview of climate change, a thorough guide for local climate change responses, and other resources, including land use and wind energy toolkits.

ENERGY STAR® Portfolio Manager

An interactive energy management tool to help local governments and businesses track energy and water consumption at the building level.

Further Reading

EPA’s Clean Energy Lead by Example Guide

Strategies, resources, and action steps for state programs, including information relevant for promoting green local government operations.

ENERGY STAR® Strategies for Buildings and Plants

Proven energy management strategies and no-cost tools for local and state governments.

DOE SunShot Initiative: Solar on Municipal Facilities WebinarExit

An hour-long webinar that shares the experience and lessons learned of three cities that have successfully installed solar on city-owned facilities.

Baton Rouge Sustainable Government Operations Plan (63 pp, 1.15 M, About PDF) Exit

From the Parish of East Baton Rouge, a plan that provides a framework for integrating energy efficiency and resource sustainability into government services, facilities, and daily operations.

Green Illinois: Green Governments Coordinating CouncilExit

Created in 2008 to help state agencies, boards, and commissions adopt a greener way of delivering services.

Acknowledgements:

EPA would like to acknowledge Liz Compitello (Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission) and Peter Ludwig (Elevate Energy, Illinois) for their valuable input and feedback as stakeholder reviewers for this page, as well as Chris Carrick, Sam Gordon, and Brian Pincelli (Central New York Regional Planning and Development Board) for their contributions to the Preble, New York, case study.