Adopt a Policy

These guidelines are intended to assist local entities that want to drive change in their community by adopting an ordinance, plan, or other type of policy. By setting a policy, local entities can require specific actions to achieve concrete objectives, affect the behavior of local residents and businesses, and drive change. Projects to adopt a policy might include:

- Adopting policies to improve energy efficiency in residential or commercial buildings (e.g., building codes, time of sale ordinances, expedited review of green buildings).

- Adopting policies to promote renewable energy production or consumption (e.g., removing obstacles to renewable energy siting, green power purchasing, solar panel permitting standards, wind siting polices, solar access policies).

- Adopting sustainable land use policies (e.g., parking maximums, conservation districts, mixed-use districts, agriculture protection districts, green space requirements, permeable pavements).

- Adopting policies to reduce waste (e.g., mandatory recycling or composting, construction and demolition waste recycling ordinance, environmentally preferable purchasing policies, permit rain gardens, water recycling standards).

- Adopting policies to promote greener transportation (e.g., anti-idling restrictions, “complete streets” policies, low sulfur diesel fuel requirements for construction vehicles, establishing bicycle parking, density bonuses for high-quality bicycle facilities).

- Adopting policies to promote infrastructure resilience (e.g., freeboard requirements that take into account anticipated changes in flood frequency, cool-roof ordinances).

The following key steps describe how to put in place a new or updated policy and how to ensure compliance with the new policy, including best practices and key questions to consider. Information on adopting policies that apply only to internal government operations is covered under Promote Green Government Operations. Programs related to incentivizing or otherwise encouraging behavior changes in the community are covered under Engage the Community; however, to the extent that any rulemaking or other policy-enacting action is required to initiate these programs, that material is covered here.

To be connected with a local representative with experience adopting climate, energy, or sustainability policies, contact us.

Key Steps

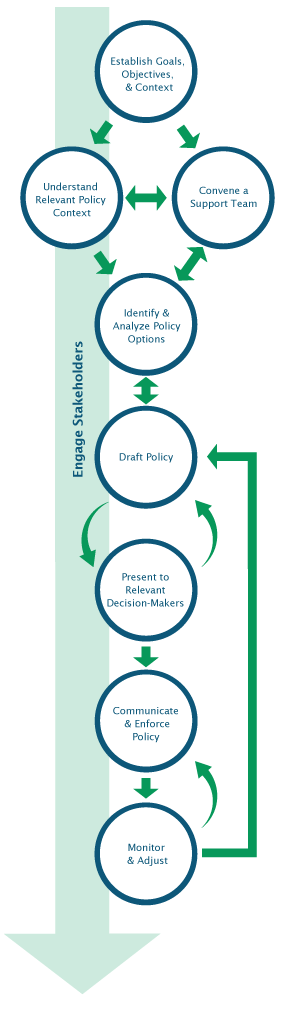

Exact processes for adopting new policies will vary by entity and topic. However, some general guidance applies, regardless of the exact policy-adopting protocol. The following guidance outlines the general steps involved in adopting and enforcing a new climate, energy, or sustainability policy in your community.

The steps in this process are not necessarily intended to be pursued in linear order, as illustrated in the diagram. For example, engaging stakeholders and reaching out to experts may occur throughout the process of adopting a policy, which may go through several iterations before policies are implemented. Additionally, several steps in the process are fluid; you may find yourself moving back and forth between them, as indicated by the double-sided and curved arrows in the diagram.

- Step 1: Establish Goals, Objectives, and Context

Before embarking on a process to adopt a policy, first clarify the exact goals of the policy and the objectives it is designed to achieve. These goals may derive from a higher-level plan (such as a climate change action plan or comprehensive plan), or from other policy drivers in your community. For example, a policy goal may be to reduce residential energy use or to incorporate climate considerations into a specific ordinance. While high-level goals are important as policy drivers, it is important to also develop goals that are as specific as possible, with quantitative targets and defined audiences, when possible. See the Set Goals & Select Actions phase for additional information on the goal-setting process.

Define the problem statement that your policy seeks to address. Also, begin to develop an understanding of the local context surrounding the policy, such as the level of community support for the policy and what groups may have the strongest interest in it.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: In 2006, the Borough of West Chester, Pennsylvania, (1.8 square miles, pop. 18,000) established an ad-hoc committee to focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The committee, known as Borough Leaders United for Emissions Reduction (BLUER), began by conducting a baseline community-wide greenhouse gas inventory. The GHG inventory showed that electricity use was a primary cause of emissions in the community, so BLUER identified energy efficiency as a key mechanism to reduce emissions.

BLUER set a goal of reviewing West Chester’s building and zoning codes to identify opportunities to improve energy efficiency. This effort would contribute to BLUER’s overall goal of reducing emissions 10 percent below 2005 baseline levels by 2015.

- Step 2: Understand Relevant Policy Context

Before drafting a new policy, clearly understand the details of relevant policies at your organization and the overall policy context. A solid understanding of local community dynamics will also be important to policy adoption.

Determine whether the policy you want your community to adopt aligns with existing policies. Begin by reviewing the existing policies to understand exactly how they are structured. Consider whether the new policy would be an outright replacement of an existing policy or an update to an existing policy (e.g., whether you would need to change a whole section of municipal code or just a few lines). If the policy you want to adopt does not fit as an update to an existing policy, review any policies that may relate to the new policy to ensure they are compatible.

Understand how the new policy interacts with existing state, federal, and other relevant laws and policies. Ensure that your jurisdiction has authority to adopt the policy in mind. If you are not sure how to find this information, contact the legal department of your organization. You might also consult with professional associations like the American Planning Association, which may have dealt with a particular policy and have advice on legal aspects.

Continue to develop an understanding of the local context surrounding the policy, asking questions such as:

- What interest has the community expressed in this policy?

- What groups will support, oppose, or want to know more about this policy?

- What do you know (or can you find out) about the interests of the governing body as they relate to this policy?

- Has your jurisdiction tried to adopt this policy before?

- How will this policy be perceived in your community?

- Is there an important timeframe for adopting this policy?

Identify and engage stakeholders who can help you answer these questions and build support for the policy. Stakeholders may include community leaders, business owners, residents, and anyone who may be affected by the policy. Engage these stakeholders early and often throughout the process. See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for additional information on engaging stakeholders. Informal meetings with community leaders can be a good way to start the process, discuss these issues, and build early support for the policy.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Shortly before BLUER made plans to adopt an energy efficiency policy, the West Chester mayor surveyed residents and found that environmental issues were a high priority for the community. This indicated community support for BLUER’s efforts, which BLUER could leverage as they made the case for revised codes.

BLUER identified two primary ways to affect building energy use through local codes: by revising the building energy efficiency code, which would require approval from a state committee, and by updating conditional use criteria within the local zoning code. They conducted research to understand what would be involved in pursuing either approach.

They also began reaching out to key stakeholders to begin to understand community perspectives and build support for an energy efficiency policy. In particular, they met early on with members of the Borough Council and the building community to determine whether they would have any concerns about a new energy efficiency policy.

- Step 3: Convene a Support Team

Small Cities Climate Action Partnership Solar Procurement TeamTo shepherd the policy-adoption process and clearly delineate roles and responsibilities, consider convening a leadership or support team. Would your efforts benefit from a leadership team? Ask yourself:

Small Cities Climate Action Partnership Solar Procurement TeamTo shepherd the policy-adoption process and clearly delineate roles and responsibilities, consider convening a leadership or support team. Would your efforts benefit from a leadership team? Ask yourself:- Is the level of effort sufficiently large?

- Is the policy context sufficiently complex?

- Is the group of affected stakeholders sufficiently large/varied?

- Could existing teams or venues fulfill this role (e.g., ongoing departmental meetings, stakeholder groups for ongoing planning processes)?

- Are you or your stakeholders facing any time constraints?

If you determine that a leadership or support team would be beneficial, keep the following questions in mind when forming the team.

How large should the team be? Should the team include people only within my organization? What role should each team member play?

Depending on the size and scope of the policy you are adopting, the appropriate team may range from one to two people within your organization to a larger advisory committee made up of people from your agency or other local government agencies, community leaders, and relevant stakeholders. In determining the appropriate team, consider the various attributes and strengths of potential stakeholders. Consider individuals who offer valuable input, have important buy-in status, offer enthusiastic support, demonstrate leadership, and have unique experiences or perspectives. You will likely want to start the research into policy options (see Step 4) before finalizing your team. Steps 3 and 4 of this process will likely be somewhat iterative.

Consider establishing an internal core team that can think through the policy approach. Then, depending on the situation, determine the best approach to engage with a broader range of stakeholders. You might establish a formal community engagement process or you might identify and meet more informally with key community stakeholders individually or convened as a group.

Keep in mind that a smaller-scale policy with low barriers to adoption (such as a small update to the building energy code in a community that supports energy efficiency) may require a smaller team, while the adoption of a major plan (such as a climate change action plan) may benefit from broader input from the community.

Can you partner with other communities or a regional organization to reduce the resources required to adopt a policy?

Think about whether any neighboring communities or regional organizations could be partners in the effort. Partnerships can reduce the resources required from your organization and can also impact sustainability or resilience on a broader scale. First, consider whether your neighboring cities might be stakeholders in this process, either because they may be affected by your policy or because they might have an interest in exploring the policy with you and possibly adopting it simultaneously. If so, consider:

- Seeking out a regional organization (such as your regional planning commission) that could help you streamline coordination and communication across multiple cities or that could adopt their own policies and procedures to encourage broader adoption of the policy.

- Gathering staff members from a group of small cities to meet on a regular basis to exchange ideas, share resources, and track progress. If the cities have common goals, they can work together to draft and adopt policies in a resource-effective way. Be aware that working with this kind of formal, multi-jurisdictional group can be time-intensive.

Several collaborative partnerships formed through the EPA Climate Showcase Communities Program proved to be successful:

- Small Cities Climate Action Partnership - Four California localities collaborated on resolutions and policies.

- New Jersey Sustainable Energy Efficiency Demonstration Projects – Three New Jersey localities collaborated on adopting climate change action plans.

- Central New York Climate Change Innovation Program – The Central New York Regional Planning and Development Board worked with seven municipalities on adopting climate change action plans and implementing clean energy demonstration projects.

Helpful Tip:

Helpful Tip:Regional collaboration (through a third-party coordinator or through direct cooperation between city staff) can successfully lead to the adoption of a policy. However, some common pitfalls include jurisdictions that feel they are competing with each other, complications meeting grant reporting requirements, or partners losing interest over time. Building trust and good personal relationships, establishing clear goals and partnerships early in the process, and creating structured timelines and communication processes can help overcome these challenges.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: In West Chester, the five-member BLUER committee, tasked with reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the community, led the effort to adopt an energy efficiency policy. The volunteer committee was composed of two residents, one representative from the local university, one business owner, and one county facilities representative. The committee was formed (2 pp, 90.8 K, About PDF) Exit by the Borough Council to implement West Chester’s commitment through the ICLEI Cities for Climate Protection Campaign.

BLUER now has a formal recruitment and application process to select new members, but the committee formed informally at the start. The first committee member reached out to contacts and used personal networks to identify interested individuals. Volunteer committee members were committed to greenhouse gas reductions in West Chester and dedicated their personal time to the committee’s work. The committee decided that, given the anticipated scope of the policy—an update to an existing policy with high community support—no additional leadership team was needed.

- Step 4: Identify and Analyze Policy Options

With a clear understanding of your organization’s community and policy context, identify and evaluate options for your new policy, including enforcement mechanisms.

Other communities may have adopted policies similar to the one you are pursuing. Seek out related policies (e.g., model ordinances) that have been adopted in communities comparable to yours in ways relevant to the policy (e.g., challenges, government organization, population). Use the identified policies as inspiration and fodder as you structure your own policy. Reach out to your counterparts at other organizations and ask about best practices and lessons learned. Some ideas for research strategies:

- Contact someone who has done what you want to do, and talk with them about the challenges and opportunities they faced. If you are not able to identify anyone with relevant experience, contact us, and we can connect you with someone with valuable experience. You might also consult with professional associations like the American Planning Association, which may have dealt with relevant policies.

- Review databases for examples of policies previously adopted by states and cities. Databases include:

- University of Denver’s Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute’s Sustainable Community Development Code FrameworkExit: Provides ideas for municipal and regional codes to address a full range of sustainability issues, including green infrastructure, water conservation, coastal hazards, transportation (e.g., transit-oriented development, complete streets, bicycle mobility, public transit, and parking), community health, affordable housing, food, renewable energy, and energy efficiency.

- N.C. State University’s Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy (DSIRE)Exit: Includes local policies, searchable by geography and/or policy type.

- Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s Municipal Laws DatabaseExit: Includes nationwide municipal green building laws that apply to public and private buildings; nationwide local green building incentives; and New York State municipal green building, alternative energy, and energy efficiency laws.

- EPA’s Heat Island Community Actions Database: Includes more than 75 local and statewide initiatives (including ordinances, building codes, and incentive programs) to reduce heat islands and achieve related benefits.

- American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s Local Energy Efficiency Policy Case StudiesExit: Provides comprehensive information on energy efficiency policies and programs implemented in dozens of localities around the United States.

- EPA’s State and Local Climate and Energy Program: Provides technical assistance, analytical tools, and outreach support to state, local, and tribal governments.

- Georgetown Climate CenterExit: Resources to advance effective policies in the United States that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and help communities adapt to climate change. Includes a searchable adaptation clearinghouseExit and a collection of state and local adaptation plansExit.

- Review model plans and ordinances, which provide a template for crafting your own policy. They are available in several databases:

- Alameda County’s StopWaste.org Policy Tools and Model OrdinancesExit: Includes models for a construction and demolition debris recycling ordinance, a civic green building ordinance, a green building resolution, and an environmentally preferable purchasing policy.

- Green Cities CaliforniaExit: Includes best practices and examples of sustainability policies related to energy, environmental health, transportation, urban design, urban nature, waste reduction, and water.

- Sustainable Cities Institute Model Policies and LegislationExit: Includes model policies and legislation covering general sustainability, land use, transportation, buildings, energy, materials management, water, green infrastructure, economic development, community engagement, and food systems (e.g., Traditional Neighborhood Design Ordinance from Covington, Georgia).

- Columbia Law School Model OrdinancesExit: Includes models for municipal green building ordinances, municipal wind siting ordinances, and small-scale solar siting ordinances, along with supporting material.

- Minnesota GreenStep CitiesExit: Includes model ordinances related to sustainable development and land use, including energy efficiency, landscaping, solar energy standards, agriculture and forest protection districts, mixed-use districts, pedestrian-oriented districts and corridors, transit-oriented development, stormwater control, wind energy, and others.

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission Renewable Energy Ordinance FrameworksExit: Provides frameworks for municipalities to develop ordinances to govern the siting of small-scale solar, geothermal, and wind systems.

- Review guidance from other organizations on larger-scale planning efforts:

As you research options, evaluate multiple alternatives. For example, if your goal is to improve the energy efficiency of commercial buildings, compare the implications of alternatives for a building energy code, such as:

- Applying the code to new construction vs. major renovations

- Setting requirements for all properties vs. under-performing properties

- Determining what events “trigger” requirements (e.g., definition of “major” renovations, time of sale, a specific date for all properties)

- Setting the code into effect on one date vs. another

- Updating the building efficiency standards vs. requiring all buildings to be Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) certified

- Determining the appropriate energy requirements, factoring in your climate zone and other relevant state or national targets

- Alternatives for enforcement mechanisms

Use your research on existing policies to inform which alternatives to evaluate.

For each alternative, consider the costs, benefits, and societal impacts of the policy, as well as any needed support and enforcement. Select the best alternative based on your goals (e.g., largest reductions in energy use, lowest cost and complexity, impacts to the greatest number of people), while keeping in mind the direct impacts on those most affected by the change in policy. You can use this comparative information to support your policy decision. Additional information on evaluating actions is available under Step 5 of the Set Goals & Select Actions phase.

Helpful Tip:

Helpful Tip:Remember to keep stakeholders engaged throughout the process.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: The West Chester, Pennsylvania, BLUER committee researched several policy options for addressing energy efficiency in buildings, thinking through the entire process of how buildings are constructed to identify policy opportunities. For example, the committee considered attempting to update the energy efficiency code versus adding an energy efficiency criterion to the borough’s conditional use criteria in the zoning code. The committee opted to pursue changes to the conditional use criteria because of the political and practical barriers involved in changing energy codes, which requires approval from a state committee.

Within the conditional use criteria, BLUER also considered several options for promoting energy efficiency, including ENERGY STAR, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Green Globes, and other programs. Ultimately, West Chester pursued an addition to the zoning code’s conditional use criteria that required buildings to earn an ENERGY STAR label.

According to BLUER chair Dianne Herrin, ENERGY STAR was the “clear choice” for West Chester. ENERGY STAR most directly addressed energy efficiency, the goal of the policy, with minimal burdens for developers in the small town.

BLUER continued to engage community members and decision-makers throughout this process. They prepared a brief (10-minute) presentation to give to the Borough Council, developer community, and building managers, discussing the benefits of energy efficiency in buildings and building support for the policy.

- Contact someone who has done what you want to do, and talk with them about the challenges and opportunities they faced. If you are not able to identify anyone with relevant experience, contact us, and we can connect you with someone with valuable experience. You might also consult with professional associations like the American Planning Association, which may have dealt with relevant policies.

- Step 5: Draft Policy

Once you have analyzed the alternatives, draft a policy that works for your community. This may be largely identical to one of the policies you reviewed, a combination of elements from various existing policies, or may include completely new elements or structures. When drafting the policy, consider which format would be most appropriate and follow your entity’s policy-making procedures. Keep in mind that policies can take many forms, including a formal plan, an ordinance to put forward by the city council, or a recommendation memo to the decision-making body.

As you draft the policy, consider the following questions:

How will the policy be implemented and who would be responsible for implementation?

As you are drafting the policy, think through who will be responsible for implementing the policy. If appropriate, include this language in the policy itself.

For example, the City of Austin drafted (and adopted) an ordinance to require properties in Austin to undergo energy audits before the sale of a property. The ordinance itself placed the director of the Austin Electric Utility (the public utility and a city department) with the responsibility of implementing the policy.

How should the policy be enforced and who would be responsible for enforcement?

Think about how the policy will be enforced, who will be responsible for enforcement, and whether to include that language in the policy. Examples of enforcement mechanisms include establishing periodic audits, fines for non-compliance, and others. Model ordinances or plans are good places to look for examples of how other jurisdictions have enforced similar policies.

How much would policy implementation and enforcement cost? What funds could cover these costs?

In determining the most appropriate implementation and enforcement mechanisms for the policy, keep in mind the relative resources required for the different options. Determine whether existing staff and responsibilities could cover enforcement. For example, if the policy adds requirements for new construction in the community, check to see if existing code enforcement functions could include enforcement of the new policy in the context of their existing roles and capacity, or if additional funds or staff would be required to carry out enforcement of the new requirements. If the policy requires ongoing activity, try to identify ongoing funding to cover that activity (not a one-time grant). See the Obtain Resources phase for information on securing staff time, funding, or other resources to implement and enforce the policy.

As you draft the policy, build your justification. Consider developing a formal document that you can use to support the proposed policy and the way it is structured. The justification document might include an alternatives analysis documenting the analysis done in the previous step and the reasons for the selections you made. It may also include sections related to the policy’s fiscal impacts, legal issues, sustainability issues, or other metrics that are important to consider when proposing any policy.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: The West Chester BLUER committee members drafted an ordinance to bring before the Borough Council. The ordinance amended West Chester’s zoning code to require that any developers seeking a “conditional use” approval for a project must design the buildings to meet ENERGY STAR energy performance goals. In West Chester, conditional use approvals are required for any buildings taller than 45 feet. Within one year of operation, having done the upfront work to design to ENERGY STAR standards, building owners could assess energy use and apply for the ENERGY STAR label and recognition. The new requirement to design to ENERGY STAR standards was added to the list of other conditional use criteria required to receive a building permit, such as parking, lighting, and signage requirements. The municipal legal counsel provided support in drafting the language of the ordinance.

The policy is available online at: See § 112-33.1 of the policyExit.

- Step 6: Present to Relevant Decision-Makers

Now that the policy is drafted and you have informally engaged with decision-makers throughout the process, formally present the policy to the relevant decision-making body to consider for adoption. Follow your entity’s procedures. Anticipate any questions about the policy and be prepared to summarize the problem or opportunity you are trying to address, the process you have gone through to arrive at your recommendation (including how you have engaged stakeholders and any input received), the content of the proposed policy, how the policy will be implemented and enforced, who will be responsible for implementation and enforcement, how it would impact the agency in terms of cost and staffing, why they should adopt it, and any other relevant issues such as urgency, potential alternatives, etc.

If the policy is adopted, you can move on to implementing the policy.

If the policy is not adopted, consider whether it is appropriate to revise, address concerns, and try again. Keep stakeholders engaged as you make these decisions.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Once a final draft of the ordinance was complete, BLUER followed the Borough Council’s protocol to present it for a vote. They published a public notice in the local paper about the proposed ordinance, held a public hearing, and had the ordinance put on the agenda for the next Borough Council work session. At the work session, council members reviewed and discussed the ordinance, and BLUER members answered their questions. Since BLUER had already briefed the Borough Council using their 10-minute presentation and proactively addressed their concerns, BLUER faced very few questions and little to no resistance from the council. After presenting it to the council, the proposed ordinance was moved to the voting session the following week, where it passed unanimously. In total, the process to adopt the ordinance took about six months.

- Step 7: Communicate and Enforce Policy

Gila River Indian Community staff conducting a recycling audit in April 2012.Once the policy has been adopted, consider the following questions:

Gila River Indian Community staff conducting a recycling audit in April 2012.Once the policy has been adopted, consider the following questions:Who needs to know about the new policy for it to take effect?

Communicate about the policy to affected parties. These may be individuals within city or government departments, the building community, business owners, homeowners, or others.

What do they need to know for the policy to take effect?

If the policy requires people to adopt new behaviors, make sure they know how to comply with the policy. It may make sense to hold trainings on the new policy for people affected. For example, Sacramento developed river-friendly landscaping standardsExit and held a series of trainings with park staff and local landscape architects to inform them of how the standards work.

Enforcement can take many forms, and can also evolve with time as you better understand how the public is responding to the policy (see Step 8).

See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for additional tips on conducting outreach and communicating policies. See the Obtain Resources phase for information on securing staff time, funding, or other resources to communicate the policy.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Once the council passed the policy, BLUER issued a press releaseExit and organized a training session for local building managers and developers about the ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager software. They also prepared a checklist for the zoning officer to distribute to all relevant building permit applicants, including background information on the ordinance, a checklist of tasks necessary for compliance, and resources. These efforts made sure that builders knew exactly what was expected of them and how to comply. Enforcement of the policy fell to the zoning officer who now considers the ENERGY STAR requirements in addition to other conditional use requirements in granting building permits.

- Step 8: Monitor and Adjust

Once in place, monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the policy and make any needed adjustments. Periodically revisit the policy to adjust it based on changing conditions in the community. For example, as green building practices become more standard, you might want to adopt a revised green building policy with more stringent performance thresholds.

Also be prepared to refine your communication and enforcement strategies over time, if necessary. For example, San Francisco changed the enforcement of its 2008 composting ordinance from a fine-based system to an outreach approachExit in response to public resistance to fines.

Visit the Track & Report phase for additional information.

Case in Point:

Case in Point: Though West Chester, Pennsylvania, has not implemented any formal monitoring and evaluation efforts related to their ENERGY STAR ordinance, the new policy has been successful, and all private buildings built since the passing of the ordinance have exceeded ENERGY STAR standards. On average, ENERGY STAR certified buildings and plants use 35 percent less energy and cause 35 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions than comparable buildings across the country. However, West Chester has noticed that it is difficult to fully evaluate the benefits of the ordinance in its current form, since builders are not required to earn the ENERGY STAR label; they are required only to demonstrate that the building is designed to ENERGY STAR standards. Five years after the initial policy was passed, the borough is now considering strengthening the ordinance to make it easier to document the energy benefits.

Case Studies

Austin, Texas: Energy Conservation Audit and Disclosure OrdinanceExit

Ordinance that requires properties within the city or served by the public utility to undergo energy audits before the sale of the property.

Salt Lake City, Utah: Idle Free OrdinanceExit

Information about an ordinance that prohibits unnecessary vehicle idling over two minutes within city limits.

New York City, New York: Car Share Zoning Text AmendmentExit

New York City’s amended city zoning resolution that allows car share vehicles to park in off-street parking garages and lots.

Bellingham, Washington: City Council Resolution to Start a Municipal Green Power Purchasing Program (136 pp, 928 K, About PDF)Exit

Resolution to launch a municipal green power purchase program (pp. 97–99 of the Compendium of Best Practices).

Chicago, Illinois: Landscape OrdinanceExit

Ordinance that requires developers to include landscaping in their building plans to reduce urban heat and air pollution promoting adaptation.

Tools and Templates

Minnesota Model Ordinance for Transit-Oriented DevelopmentExit

Clearinghouse of model ordinances related to sustainable development, transportation, and land use.

DOE’s Building Energy Codes Program, Adoption ProcessExit

From the U.S. Department of Energy, information on how to adopt building energy codes, including technical assistance and information on state energy codes.

Smart Growth Implementation ToolkitExit

From Smart Growth America, a tool for local governments looking to adopt smart growth land use planning and community design policies; includes a policy audit that could support Step 2.

Alameda County, California: Construction & Demolition Debris Recycling Model OrdinanceExit

Model ordinance from the StopWaste.org clearinghouse that requires recycling of construction and demolition debris.

Columbia Law School Model Municipal Wind Siting OrdinanceExit

Model ordinance for siting wind energy, including provisions for permits, approvals, operation, and oversight of wind energy conversion systems.

Further Reading

University of Denver, Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute’s Sustainable Development Code FrameworkExit

Framework that provides ideas for municipal and regional codes to address a full range of sustainability issues.

Local Energy Planning in Practice: A Review of Recent Experiences (49 pp, 5.77 K, About PDF) Exit

From the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a report that reviews the energy efficiency planning activities of 30 local governments, including commonalities and opportunities for improvement.

EPA’s National Clean Diesel Program

Information, tools, program design resources, and regulatory standards related to regional clean diesel collaboratives.

EPA’s Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies

Guide that describes measures that communities can take to address the impacts of urban heat islands, including voluntary and policy efforts.

Acknowledgements:

EPA would like to acknowledge Garrett Fitzgerald (City of Oakland, California) and Jeff Perlman (North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority) for their valuable input and feedback as stakeholder reviewers for this page, as well as Dianne Herrin (BLUER) for her contributions to the case study.