Sustainable Financing Examples from the National Estuary Program (NEP)

This page highlights examples of successful finance mechanisms being used by the National Estuary Programs (NEPs).

Funding Mechanisms Used by the National Estuary Programs

| National Estuary Program (NEP) | Funding Mechanism | Amount of Funding | Use of Funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership for the Delaware Estuary | Annual Appeal | $29,779 in 2005 | General support |

| Casco Bay Estuary Partnership (ME) | Special Appeal | $56,000 | Lobster habitat study and relocation effort |

| Narragansett Bay Estuary Program (RI) | Grant and Partnership | $600,000 | Habitat restoration |

| Indian River Lagoon NEP (FL) | License Plate Program | $400,000 annually | Habitat restoration and environmental education |

| Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program (TX) | Supplemental Environmental Project | $1.5 million | Land acquisition and habitat restoration |

| Peconic Estuary Program (NY) | Real Estate Transfer Tax | $169 million through January 2004 | Land preservation |

| Tampa Bay Estuary Program (FL) | Interlocal Agreement | At least $415,000 annually | Bay restoration and water quality improvements |

Partnership for the Delaware Estuary's Annual Appeal Pays Off

As a nonprofit organization, the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE) found that it is critical to have a broad base of funding support that includes both restricted and unrestricted funding sources. The PDE struggled with early disappointing returns from their annual appeals. They learned to fine tune their efforts, however, and have since made annual appeals a key part of their funding strategy.

When the PDE began its annual appeal program, it faced a number of challenges. It was a new organization. In addition, it works in a large, tri-state region to protect a resource (the Delaware Estuary) that was not well known.

To build support for the PDE, the director and staff strategically established relationships with Delaware Estuary stakeholders through its program activities. The PDE found that organizations and individuals involved with its activities were much more likely to offer it financial support.

In 1999, the PDE instituted its annual appeal campaign using funding from a foundation grant for capacity building. In the campaign, the PDE sent a generic appeal letter to the 25,000 people on the organization's mailing list. These people received the PDE's quarterly newsletter and an appeal for donations. Unfortunately, the results of this large mailing were disappointing.

In 2000, the PDE scaled back the appeal mailing. It sent personalized appeal letters, an annual activity report and an appeal return envelope to past donors and a select group from the mailing list (less than 1,000 people).

In 2001, the PDE further targeted its annual appeal with the help of a fundraising consultant. For its 2001 appeal, they segmented the mailing list into four different target groups:

- Past givers.

- Lapsed and never givers.

- Board member contacts (with the letters signed by the board member).

- Board members.

Each group received different letters and program materials.

The PDE also decided to give a set of estuary-themed note cards (purchased wholesale from a publisher) to any donor that made a contribution over $75. This model returned the best results: 57 gifts totaling $9,969, for an average gift of $175.

Since 2001, the PDE has continued to segment the annual appeal mailing. Financial supporters from the previous year are asked to consider increasing their gift annually. The PDE also conducts a second mailing in the spring to past givers who did not respond to the fall letter. Those who donate over $75 receive a specially designed set of note cards.

Becoming more strategic about their annual appeal campaign, combined with establishing the PDE's reputation, resulted in a steady increase on the return from the annual appeal campaign. In 2005, the Partnership received a total of $29,779 in donations from 183 people, for an average gift of $163.

Several years of trial and error have taught the PDE some valuable lessons:

- It costs money to make money and can take many years to see a positive return.

- Costs that are typically incurred include staff time, printing, postage and giveaways.

- An annual appeal is not a quick fix for raising unrestricted revenue, but rather a fundraising mechanism that can build and pay off over time.

- Appeals should be as specific and personal as possible.

- Appeals should be sent on a consistent schedule.

- Generally, people are more likely to give toward the end of the calendar year, because they are in a giving mood and are looking for tax deductions.

- Recognizing donors is very important. The PDE lists everyone who donates to the annual appeal in its activity report.

For more information, please visit Partnership for the Delaware Estuary Exit.

Casco Bay Estuary Partnership (ME) Launches Special Appeal to Save Juvenile Lobsters in Portland Harbor

Local lobstermen expressed concern that the Portland Harbor dredging project would disrupt lobster habitat. To evaluate this theory, immediate research was necessary.

The Chair of the Board for the Casco Bay Estuary Partnership (CBEP), a City Manager, wrote special appeal letters to harborfront property owners, businesses and the cities of Portland and South Portland. The letters asked for financial support for research to address lobstermen's concerns and keep the harbor dredging project on schedule. In addition, CBEP requested support from the Maine Department of Transportation. Within three weeks, CBEP raised $56,000 to conduct the lobster research and a relocation effort.

Prior to the dredging of Portland Harbor, CBEP used money from this special appeal to study lobster habitat using underwater video surveys of proposed dredge areas. Lobsters were thought to live near the shore in warm weather and move to deep-water burrows offshore in the winter. Therefore, most stakeholders believed that a winter dredging operation would have a minimal impact on lobster populations.

The videos revealed that the harbor provides winter habitat for a significant population of juvenile lobsters that burrow in the Portland harbor mud.

Consultants then developed a dredging mitigation plan that included an innovative lobster relocation effort. Before dredging began, a coalition of lobstermen, state regulators and staff and volunteers from CBEP and Friends of Casco Bay moved 34,012 small lobsters from the dredge area. This group also tagged 4,000 lobsters to help evaluate the project's success.

Left: A marine biologist assistant makes a small cut and inserts a tiny metal anchor into the lobster's muscle. The anchor is attached to a tag that has a number matching the information recorded. The tag also has a toll free phone number that lobstermen can call when one of these lobsters gets trapped. This allows the lobsters travel patterns to be recorded.

For more information, please visit Casco Bay Estuary Partnership Exit.

Narragansett Bay Estuary Program (RI) Partners to Secure Grants to Protect the Watershed

Forming partnerships are often crucial to successful grant applications. Combining forces and committing to collaboration (and sharing credit!) make for more attractive funding proposals and a stronger voice for watershed protection and restoration. In this example, the Pew Charitable Trusts funded a proposal submitted by Save The Bay, a 501(c)(3).

Save The Bay strengthened its application by demonstrating a strong partnership with the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program (NBEP), a university-based watershed restoration effort. In turn, Narragansett Bay used their partnership with Save The Bay to leverage additional state and federal grant funds.

In 1996, Save The Bay and NBEP embarked on a series of projects to construct an inventory of the state's coastal habitats. This effort included bringing the data into GIS mapping systems. Both partners took advantage of their organizational structure and staff skills to secure funding and implement habitat restoration projects.

Save The Bay successfully applied to the Pew Charitable Trust for grant funding that was available to partners in the Restore America’s Estuaries coalition. Pew Charitable Trusts contributed $200,000 to support habitat assessment and restoration projects in Narragansett Bay undertaken by Save The Bay and NBEP. The two groups used the foundation money as match for state and federal grants, which provided an additional $400,000 for Narragansett Bay habitat restoration efforts.

Save The Bay successfully applied to the Pew Charitable Trust for grant funding that was available to partners in the Restore America’s Estuaries coalition. Pew Charitable Trusts contributed $200,000 to support habitat assessment and restoration projects in Narragansett Bay undertaken by Save The Bay and NBEP. The two groups used the foundation money as match for state and federal grants, which provided an additional $400,000 for Narragansett Bay habitat restoration efforts.- map critical eelgrass beds, salt marsh habitat areas and coastal features

- hire technical staff to identify potential restoration sites and develop restoration plans

- launch an extensive public information campaign

This collaboration also helped form the Rhode Island Habitat Restoration Team. The team is an ad hoc, but highly effective, partnership that has shaped goals, identified projects and attracted additional funding for coastal habitat restoration. Moreover, their efforts include the creation of a dedicated state fund for restoration projects.

For more information, please visit Narragansett Bay Estuary Program Exit.

This eelgrass mariculture facility was constructed in 2004 with EPA Targeted Watershed Initiative grant funds. It is one of the results of a partnership effort between NBEP, University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography and Save The Bay to restore critical bay habitat.

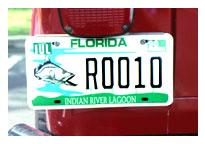

Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (NEP) (FL) Uses License Plate Revenue Supports Environmental Education and Habitat Restoration

The Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (NEP) led the development and management of the Indian River Lagoon specialty license plate revenue program. To establish the program, the Indian River Lagoon NEP took the following steps:

- First, the Program collected petitions containing the signatures of 12,000 registered Florida vehicle owners who agreed they would purchase the specialty plate when available.

- Second, the Program obtained the support of a Florida state representative and a state senator who agreed to sponsor the Bill to create the specialty plate.

- Third, the Program paid a $15,000 one-time administration fee to the Florida Department of Motor Vehicles. Short- and long-term marketing strategies were also developed as required by the Department of Motor Vehicles.

The Indian River Lagoon NEP is responsible for the promotion of the Indian River Lagoon license plate and management of the grant program supported by its revenues. Several corporate partners have supported the Indian River Lagoon's promotional campaign for the license plate. Many McDonald's franchises throughout the lagoon's watershed helped gather signatures at the start of the campaign.

The Anheuser Busch Corporation donated $15,000 to help pay for the production and labor costs of more than 70 billboard advertisements. The Florida Outdoor Advertising Association donated $60,000 worth of billboard advertising space. For three months, a local car dealership provided all new car buyers with Indian River Lagoon license plates.

For each lagoon license plate sold or renewed, the Indian River Lagoon NEP receives $15. During the first seven years, the license plate raised more than $4 million. The Program continues to receive about $400,000 annually. Because the vehicle owners pay the fee annually, this program provides a relatively stable source of continuing funding.

At least 80 percent of the Indian River Lagoon's specialty license plate proceeds support habitat restoration projects. Up to 20 percent support environmental education projects focusing on the lagoon. License plate revenues do not support salaries, studies or other administrative costs. Habitat restoration projects have included:

- the reconnection of impounded salt marshes

- shoreline stabilization

- spoil island and mangrove restoration

- stormwater treatment retrofits

Environmental education projects have included exhibits, videos and support for lagoon learning centers. Many diverse lagoon projects have been accelerated or made possible as a result of revenue derived from sales of lagoon license plates. These funds have leveraged more than the total revenue raised in matching funds.

The largest obstacle for this program has been competition from more than 100 other specialty license plate designs for sale in Florida. In response, the program needed to initiate an extensive marketing campaign and offer a design that was unique. The Indian River Lagoon NEP was successful in both of those areas. The initial marketing campaign was a success as a result of strong corporate partners.

The largest obstacle for this program has been competition from more than 100 other specialty license plate designs for sale in Florida. In response, the program needed to initiate an extensive marketing campaign and offer a design that was unique. The Indian River Lagoon NEP was successful in both of those areas. The initial marketing campaign was a success as a result of strong corporate partners.

Current marketing strategies include direct mail promotions to plate owners and targeted advertising in regional and statewide angler magazines. The Indian River Lagoon license plate was the first in Florida to feature a fish, the snook, which has appealed to anglers throughout the state. Currently, the lagoon license plate ranks 16 out of 103 specialty plates available for drivers to choose from in Florida.

For more information on this unique funding opportunity, please visit Indian River Lagoon Basin Exit.

Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program (TX) Receives a Supplemental Environmental Project (SEP)

Koch Petroleum (now Flint Hills Resources) provided the Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program (CBBEP) (Corpus Christi, TX) with $1.5 million for supplemental environmental projects (SEP). This funding was part of a settlement with the State of Texas and the U.S. Department of Justice. Koch Petroleum agreed to this settlement after the company had more than 300 spills of crude oil, gasoline and other oil products between 1990 and 1997 in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Louisiana and Alabama.

In the settlement, Koch Petroleum agreed to pay a $30-million civil penalty, make a voluntary contribution of $5 million for SEPs and improve its leak-prevention programs.

The CBBEP was pleased to be allocated $1.5 million during the settlement process. This funding was likely given to CBBP because the largest of Koch's spills, a 100,000-gallon oil spill in 1994, caused a twelve-mile slick within the area served by CBBEP. Two additional factors may have contributed to the selection of CBBEP as a recipient for these funds:

- The CBBEP has a long history of public involvement, including strong relationships with both industry and state government. CBBEP was well known by both Koch Petroleum and the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission.

- All parties to the settlement recognized that CBBEP could implement habitat restoration projects with very low overhead costs.

The CBBEP used the SEP funds for three land acquisition and habitat protection projects:

- The CBBEP worked with the following organizations to conserve land with high ecological value or development pressure through acquisition or conservation easements:

- The Nature Conservancy

- The Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission

- The City of Corpus Christi

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- The CBBEP partnered with the Texas General Land Office to protect six existing rookery islands and restore approximately six acres of colonial waterbird rookery island habitat in Nueces Bay.

- The CBBEP, in conjunction with the Texas General Land Office and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, planted smooth cord grass along eroding shorelines to reduce erosion and create marsh habitat. CBBEP was able to use the $1.5 million SEP to secure an additional $2.5 million in matching funds.

There were three major obstacles to this SEP:

- The State of Texas, the U.S. Department of Justice, and Koch Petroleum had to conclude that CBBEP was a suitable recipient of project funding. As noted above, CBBEP's connection to a 1994 oil spill undoubtedly influenced this decision. However, CBBEP's track record of communication with the business community and successful project implementation likely impacted this decision.

- The Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission requested that CBBEP develop a plan for $1.5 million in project funding within one month. CBBEP was able to meet this deadline with a streamlined planning process and many hours of hard work.

- The CBBEP had to implement its SEPs with these resources within 18 months. The time pressure was a particular challenge with land acquisition projects that required negotiation of a purchase price. Therefore, it was essential to have strong partners to meet this deadline.

For more information, please visit Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program Exit.

Peconic Estuary Program (NY) Helps Build Community Support for a Real Estate Transfer Tax

Since 1993, the Peconic Estuary Program (PEP) has conducted extensive public involvement and outreach in its watershed. The outcome of this work has been strong partnerships with organizations and individuals in their community. Community-based support was crucial to the establishment of a 2-percent real estate transfer tax dedicated to conserving land and other related purposes, including historic preservation.

Real estate transfer taxes are assessments made by states or local governments on real estate transfers based on the sale price of the property. These taxes are paid by the buyer of the property. Implementing the real estate transfer tax required three major steps:

- The New York Legislature needed to pass enabling legislation. State- and national-level real estate and builder lobbies opposed the real estate transfer tax and delayed passage of the enabling legislation for more than a decade. In 1998, the New York Legislature finally voted to allow Long Island's five east end towns to hold referenda on establishing a real estate transfer tax.

- Each town developed a Community Preservation Plan to identify priority parcels for acquisition and easements.

- Each town needed to pass local referenda to approve the tax. Again, real estate and builder lobbies opposed the referenda and spent $300,000 to fight its passage. Despite their efforts, all the towns successfully gained voter approval, passing with at least a 60 percent majority.

A large community-based coalition was formed and included:

- the Committee for the East End Community Preservation Fund

- PEP

- Suffolk County

- five towns

- local businesses

- realtors

- builders, citizens and others

This coalition presented a compelling case to voters that preserving open space would protect estuarine resources, groundwater quality and the character of Long Island's East End.

This case was based in part on studies done by the PEP. These studies included an economic valuation of the estuary and its impact on the local economy, detailed information of current land use and projections of development and population trends. Together, they were able to rally support for the enabling legislation and the referenda.

The 2 percent real estate transfer tax is the most successful land protection program on Long Island, and it raised over $169 million through January 2004. Using an average of 2-percent tax revenues and multiplying it through the life of the fund (end of 2020), total additional revenue should be approximately $556 million.

Many critical landscapes have been protected with funds from the 2 percent real estate transfer tax and other sources. However, current land acquisition funding is not sufficient to keep up with development rates. It is estimated that less than 10 percent of the parcels identified as critical in the Peconic watershed could be protected with future 2 percent tax revenues. Fortunately, large amounts of land can be protected through means other than land acquisition.

Some examples include:

- clearing restrictions

- clustering requirements

- rezoning

- overlay districts

- easements

- purchase of development rights

- overall better land use practices

It is estimated that the implementation of clearing restrictions and clustering requirements would protect an additional 3,491 acres in the Peconic watershed. Acquiring an equivalent amount of land would cost an estimated $382 million.

Resource: Peconic Estuary Program Critical Lands Protection Plan (PDF)(61 pp, 4 MB, November 2004, About PDF) Exit

For more information, please visit Peconic Estuary Program Exit.

Tampa Bay Estuary Program (FL) Builds Partnerships and Raises Funds with Local Governments through an Interlocal Agreement

Established in 1990, the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) has worked diligently to involve local governments and Tampa Bay area citizens in its activities. TBEP adopted a formal Interlocal Agreement in February 1998 that committed 15 partners to achieving the goals of the program's bay restoration plan. Partners included:

- city, county and state governments

- a water management district

- a regional planning council

- a port authority

- the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Goals of the bay restoration plan focus on restoring and sustaining a healthier bay that will support both recreational and commercial uses. Goals are related to improving water and sediment quality, restoring seagrass beds and coastal habitats and reducing bacterial contamination. Partners also committed to improving fish and wildlife regulation and enforcement, managing dredging and dredged material and increasing public education and involvement.

As part of the agreement, local government partners and the water management district pledged to provide financial support to TBEP. Since 2000, they have collectively provided at least $415,000 in cash each year as match toward EPA's portion of cooperative agreement funding.

The following factors contributed to TBEP's success in reaching consensus in the Interlocal Agreement. The water management district's representative on the TBEP Policy Board conceived the idea of an Interlocal Agreement and served as a strong champion of the agreement. An experienced contract attorney, the water management district's representative drafted the agreement and was instrumental in building consensus among stakeholders and overcoming obstacles in the process.

Bay-area partners had been working together on bay management and protection for nearly ten years, dating back to the first Bay Area Scientific Information Symposium (BASIS) in 1982. Several milestones followed BASIS that built a tradition of regional cooperation among bay area scientists and resource managers and enabled consensus on the Interlocal Agreement.

It was also helpful to include incentives for participation into the agreement. For example, participation in TBEP may have been spurred, in part, by a desire to ensure that TBEP followed a non-regulatory approach to resource management. Regulators agreed to extend reasonable flexibility in permitting projects of TBEP partners that helped achieve goals of the bay restoration plan.

Further, a track record of affordable implementation demonstrated that the agreement would be a good investment for the partners. It was estimated that the added cost each year to TBEP's partners for implementing the restoration plan was insignificant compared to their overall budgets.

For more information, please visit Tampa Bay Estuary Program Exit.