How the National Estuary Programs Address Environmental Issues

Because we love and depend on coastal water resources, over half the U.S. population lives within 100 miles of a coast, including the shores of estuaries. And more and more people are moving to these areas. Due to the rapid population growth in coastal areas, and climate change, estuaries face a host of common challenges.

In general, these problems cause declines in water quality, living resources and overall estuarine ecosystem health. They also have significant economic and socio-economic impacts. For example, habitat and water quality degradation, along with the introduction of aquatic nuisance species, stresses native fish species populations, which can in turn adversely affect commercial seafood production.

The 28 National Estuary Programs (NEP) share information about their successful approaches to environmental challenges with each other and other coastal watershed managers. That exchange is critical to the effective restoration and protection of estuarine health across all the NEPs.

Provided below are descriptions of the common environmental challenges NEPs face and selected NEP approaches and success stories.

Alteration of natural hydrologic flows

People alter the environment, including how water flows. With development and water-related infrastructure (e.g., dams, flood control structures, diversions), we can change the volume and rate that water runs off the landscape, into the ground and into streams.

Increased runoff can result in erosion and sedimentation. Changes in freshwater inflows to estuaries can adversely affect shellfish survival and fish reproduction and distribution.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program

Hydrologic modifications to the Mississippi River for flood control have dramatically reduced freshwater flows, and contributed to wetland losses and saltwater intrusion, in the Barataria-Terrebonne estuary (located in Louisiana).

The Davis Pond Diversion structure (upstream of New Orleans) is the largest Mississippi River diversion into the Barataria Basin. The diversion helps control salinity and enhance vegetation in the Barataria system by sending freshwater, nutrients and small amounts of sediment.

The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program represents local stakeholders on the Davis Pond Advisory Committee, which authorizes and directs the operation of the structure. The advisory committee is re-evaluating the Davis Pond operational plan so that the diversion can be operated to enhance a greater area of wetlands in the lower Barataria Basin without adversely affecting estuarine-dependent species.

Morro Bay National Estuary Program (Morro Bay NEP)

While estuaries naturally fill with sediment as part of the geologic process, the rate of sedimentation in Morro Bay (located in California) is as much as ten times the natural rate, due largely to changes caused by people. Moreover, major factors contributing to increased sedimentation in the estuary include:

- Fires

- Overgrazing

- Erosion from development

- Loss of floodplains

The estuary could lose all of its open-water and inter-tidal habitat within 300 to 400 years. Increased sedimentation also adversely affects plants and animals. Increased sedimentation in the water can bury, or partially block sunlight from reaching, eelgrass beds, destroying these underwater meadows. Sediment also buries and clogs gravel spawning beds for steelhead trout.

The Morro Bay NEP and its partners take a holistic approach to restore the natural sedimentation process by:

- Stopping sediment at the source; and

- Catching it downstream before it reaches the estuary.

As one measure to stop sediment at the source, the program developed a fire management plan to help local fire districts reduce the risk of large catastrophic fires that leave bare slopes vulnerable to erosion.

The program also teamed with the local Resource Conservation District and ranchers to improve grazing practices and to fence cattle out of creeks, further reducing erosion. To date, approximately 35 percent of stream miles in the watershed have been fenced from cattle.

In another source-control strategy, the program partnered with land owners to improve eroding ranch roads. For example, Camp San Luis Obispo road improvements, funded partially through the program, will prevent an estimated 2,800 cubic yards of soil from entering the nearby creek.

Photo credit: Morro Bay NEPFurther, floodplain restoration efforts help these areas catch sediment before it reaches the estuary. The program and its partners work to restore the expansive historic floodplains diminished by past agriculture practices. One such project, the Chorro Creek Enhancement Project, is estimated to have prevented over 150,000 cubic yards of sediment from reaching the bay.

Photo credit: Morro Bay NEPFurther, floodplain restoration efforts help these areas catch sediment before it reaches the estuary. The program and its partners work to restore the expansive historic floodplains diminished by past agriculture practices. One such project, the Chorro Creek Enhancement Project, is estimated to have prevented over 150,000 cubic yards of sediment from reaching the bay.

To date, approximately 300 acres of historic riparian floodplain have been protected or restored. These floodplains not only trap sediment from reaching the bay, but also provide important fish and wildlife habitat.

Through the program's monitoring efforts, staff are working to determine accurate annual sediment loading values for the tributaries in the watershed. The program will use this information to better target areas for project implementation and help refine the current sediment TMDL in the watershed.

Aquatic nuisance species

As the ease of transporting organisms around the globe has increased, so have the rates of intentional and accidental introduction of aquatic nuisance species (ANS). These ANS introductions often have unexpected ecosystem, economic and social impacts.

For example, ANS harm native fish and wildlife in many ways. They can take over native species' habitats, out-compete and prey upon those species and disturb entire food webs. As well, a few ways in which they affect human activities include:

- Disrupting agriculture, shipping, water delivery, recreational and commercial fishing

- Undermining levees, docks and environmental restoration activities

- Impeding navigation and enjoyment of local and regional waterways

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

San Francisco Estuary Partnership (SFEP)

The San Francisco Bay is one of the most "invaded" estuaries in the world. The San Francisco Estuary Partnership (SFEP) works to minimize the impacts of ANS by supporting efforts in the areas of planning, mitigation, prevention and detection.

For example, SFEP helped develop the California Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan, which provides a framework for responding to aquatic invasive species and protecting native plants and animals in California. The Partnership worked with the State Coastal Conservancy, the California Department of Fish and Game and other state and federal agencies involved with invasive species to complete the plan, which California's Governor signed in 2008.

The SFEP also supports the 100th Meridian Initiative, a collaboration among government, private industry and public stakeholders to prevent the westward spread of zebra mussels. The collaboration provides education and outreach on preventative measures, such as voluntary boat checks. The partnership includes the six states that straddle the 100th Meridian (100º longitude), the Canadian province of Manitoba and most of the western states.

Additionally, SFEP completed the Aquatic Invasive Species Early Detection Program, which assists watershed volunteer groups in identifying new invasions of aquatic species.

The SFEP also supported efforts to control the spread of the Chinese mitten crab. Although introduced elsewhere in the United States, Chinese mitten crabs became an established U.S. population after being introduced into San Francisco Bay. Once established, the crabs excavate and burrow into river banks, eroding those banks and damaging levees. The crab's sharp claws also cut through commercial fishing nets and reduce or damage catch.

Further, while not found in the California crabs to date, mitten crabs can host lung fluke, a parasite that causes tuberculosis-like symptoms in humans. At some California Aqueduct and State Water Project fish salvage facilities, mitten crabs clogged screens, holding tanks and transport trucks used to salvage fish from the pumping stations. To mitigate the crabs' impact, the state built "Crabzilla,” an 18-foot high traveling fish screen.

In 1998, the state transported approximately one million mitten crabs trapped by the screen to another facility that ground them up for fertilizer. By 2005, the mitten crab population in the San Francisco Bay watershed had declined considerably.

For more information, see: California Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan Exit.

Peconic Estuary Program (PEP)

The Peconic Estuary Program (located in New York) facilitates a monitoring and removal program to control the invasive aquatic plant Ludwigia peploides from the Peconic River system. First detected in the system in 2007, Ludwigia is a threat to the river because it:

- acts as unsuitable fish habitat;

- out-competes and blocks sunlight to native plants; and

- impedes recreational uses of the river.

Soon after the Ludwigia discovery, numerous stakeholders united to eradicate the plant from the Peconic River. From 2008-2012, 13 volunteer “Ludwigia Eradication” events were held, where 438 volunteers spent 2,360 hours hand pulling 130 cubic yards of the plant. To ensure this invasive plant does not re-establish in the river, the community holds annual monitoring and periodic maintenance pulls.

Puget Sound Partnership

To help prevent the introduction of new invasive species in the Puget Sound region, EPA invested $250,000 for implementation of key recommendations in the Invasive Species Council’s “Invaders at the Gate” Strategic Plan. As an example, one project assessed the 15 highest priority invasive species in the Puget Sound basin to determine their extent and distribution, as well as to identify current management practices and any management gaps.

Climate change

Estuaries face unique impacts from climate change. As sea-levels rise, increased erosion and inundation threaten many coastal wetlands and estuarine habitats. As temperatures rise due to climate change, so do stresses to habitats and fish and wildlife populations. Climate change will lead to more severe storms, which means increased polluted runoff. This runoff can further degrade water quality in estuarine waters.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

- Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program

- Long Island Sound

- Partnership for the Delaware Estuary

- Santa Monica Bay National Estuary Program

- Sarasota Bay Estuary Program

- Tampa Bay Estuary Program

See also: Climate Ready Estuaries website.

Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program (CHNEP)

The EPA Climate Ready Estuaries (CRE) program helps coastal managers:

- assess climate change vulnerabilities;

- develop and implement adaptation strategies;

- engage stakeholders; and

- share lessons learned.

With EPA CRE support, CHNEP and partner Southwest Florida Regional Planning Council developed a comprehensive report evaluating climate change vulnerabilities in southwest Florida. The team used the latest scientific information in developing the report.

In addition, the partnership developed key tools that local governments can utilize. These resources include:

- model language for local government climate change adaptation plans;

- a list of climate change environmental indicators; and

- a climate change conceptual ecological model.

The partnership also teamed with the city of Punta Gorda (in Lee County, Florida) to develop a climate change adaptation plan that reflects citizen input and community priorities. In its role, CHNEP held public workshops and facilitated the planning process, which included analyzing the city's climate change vulnerabilities, and developing mitigation strategies and adaptation techniques, as well as an implementation framework for the identified actions.

The plan underwent public, city staff and council review before it was unanimously accepted in November 2009. The adaptation plan serves as a sourcebook of ideas to make the city more resilient. Further, the city’s adaptation planning model subsequently served as a model for Lee County’s government.

These communities are taking on the complex, long-range challenge of climate change with plans that provide a basis for incremental actions. This approach can make a significant difference in the long run without tremendous upfront costs. Punta Gorda's plan includes a total of prioritized acceptable and unacceptable adaptation options as defined through group consensus.

Moreover, Punta Gorda's plan indicates which areas will retain natural shorelines and constrain locations for certain high-risk infrastructure. The community has the data and analysis, as well as a framework to consider the menu of adaptation options that make sense at any point in time.

Long Island Sound

The Long Island Sound Study sponsored the development of a strategic plan and program to detect signs of climate change in Long Island Sound estuarine and coastal ecosystems. The program, Sentinel Monitoring for Climate Change in Long Island Sound, is a multidisciplinary, scientific approach to provide early warnings of climate change impacts and develop processes to facilitate appropriate and timely management decisions and adaptation responses.

The program will base the early warnings on assessments of indicators and sentinels related to climate changes. Moreover, the program’s approach is novel in that it combines regional-scale predictions and climate drivers with local monitoring information to identify candidate sentinels of change.

Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE)

The PDE engaged experts to assess vulnerabilities and adaptation options for tidal wetlands, drinking water and bivalve shellfish. Their report, Climate Change and the Delaware Estuary, includes three case studies on climate change impacts on habitat, humans, water use and living resources.

Santa Monica Bay National Estuary Program (SMBNEP)

The SMBNEP is engaged in various climate change initiatives affecting Santa Monica Bay and Los Angeles.

Through a U.S. EPA Climate Ready Estuary (CRE) grant, SMBNEP and researchers from Loyola Marymount University developed the Study of Potential Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Wetlands. The study analyzed future conditions of coastal wetlands in Los Angeles. To do so, the team used climatic and hydrological models to simulate the impacts of various sea level and precipitation scenarios.

The results of these models are being applied to the alternatives in the Environmental Impact Report (EIR)/ Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the 600-acre Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve.

The reserve is important regionally as a stop-over for the Pacific Flyway, and restoring it will help offset the 97-percent loss of coastal wetlands in Los Angeles. The ecological restoration is being conducted with an expected 3-foot rise in sea level by the end of the century. The contours and other features of the project will allow for the transgression of habitats as the complex experiences greater inundation while providing flood protection for the neighboring communities of Venice and Marina Del Rey.

The SMBNEP helped to convene a partnership of eleven local coastal jurisdictions and organizations to launch the regional AdaptLA Project. Funded by a grant from the State Coastal Conservancy and Coastal Commission, this multi-year project will gather data and model future coastlines. The application of this work is to determine coastal vulnerability to:

- sea level rise;

- increased wave heights;

- more intense precipitation;

- storm surges; and

- El Niño Southern Oscillation.

The outputs of this work are intended to inform coastal municipalities and related agencies via a series of webinars, workshops and outreach to their constituents.

With an upcoming EPA grant, the SMBNEP will install high-precision, high-frequency pH and pCO2 sensors with project partners. The sensors will provide continuous measurements of ocean acidification (OA), helping SMBNEP understand the intensity and trend of OA in Santa Monica Bay compared to other locations along the West Coast.

With this information, project partners can explore how OA is affecting the amount, health and distribution of marine life. Lastly, these findings will help the team assess the need for the reduction of nutrients into Santa Monica Bay, from sources such as sewage treatment plants, urban runoff and aerial deposition.

Sarasota Bay Estuary Program (SBEP)

In 2014, EPA’s Climate Ready Estuaries (CRE) program prompted SBEP (located in Florida) to collaborate with Mote Marine Lab to develop the Sea Level Rise Adaptation Planning Guide. The guide provides information about basic considerations and tools to adapt to climate-related sea level rise. The audiences for the guide include the following:

- Local community leaders

- Planners

- Resource managers

- Concerned individuals

The SBEP also managed the creation of a regional Sea Level Rise Visualization Tool. The tool demonstrates projections of flooding associated with varied levels of sea level rise, in addition to storm surge effects.

The SBEP continues to engage the local community on sea level rise adaptation and resiliency planning.

Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP)

The Critical Coastal Habitat Assessment is a project to detect changes to critical coastal habitats from climate change and indirect anthropogenic impacts through a long-term monitoring program.

The monitoring will characterize the baseline (2014/2015) status of the mosaic of critical coastal habitats and can be used to detect trends in those habitats over time and assess changes in ecological function of habitats over time. The project selected monitoring locations in each of the major bay segments and two tidal river locations that have a full complement of emergent tidal wetland communities, including the following:

- Mangrove

- Salt marsh

- Salt barrens

- Coastal uplands

The project conducted a pilot assessment at Upper Tampa Bay Park in August 2014 and the methods were then refined by the Habitat Partnership. This project is part of a larger effort to manage, restore and protect the mosaic of coastal habitats critical to the ecological function of the Tampa Bay estuary.

Declines in fish and wildlife populations

The many stresses on estuaries have corresponding impacts on fish and wildlife. As their habitats disappear, the food they depend upon decreases and water quality degrades. Invasive species provide added pressures, replacing many of our native plants and animals.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

Sarasota Bay Estuary Program (SBEP)

In Sarasota Bay, historical maps and charts reveal that many once-vibrant oyster communities have disappeared. The SBEP selected for an oyster habitat enhancement project two sites that were physically disturbed and whose oyster communities were destroyed by coastal development during the 1960s.

Historical maps and charts of Sarasota Bay (located in Florida) reveal the disappearance of many once-vibrant oyster communities, which coastal development during the 1960s destroyed. To help revitalize oyster communities, the SBEP selected two sites for habitat enhancement.

The habitat enhancement effort builds upon the outcomes of an earlier pilot project, which found prospective locations for building new oyster habitats to be substrate limited. Oysters will not recover without the introduction of suitable and sufficient substrate material.

The SBEP team created a total of 4.5 acres of oyster habitat across the two sites:

The SBEP team created a total of 4.5 acres of oyster habitat across the two sites:

- 2.5 acres at White Beach in Sarasota County; and

- 2 acres at the Gladiola Fields in Manatee County.

Both locations offered opportunities to create oyster habitat where none existed. White Beach is in a highly urbanized setting where oyster beds once flourished. Over time, shoreline alterations and residential development destroyed them.

Both locations offered opportunities to create oyster habitat where none existed. White Beach is in a highly urbanized setting where oyster beds once flourished. Over time, shoreline alterations and residential development destroyed them.

The Gladiola Fields lie adjacent to suburban agricultural fields. The creation and restoration of oyster habitat in these areas should improve local water quality by filtering urban stormwater runoff and nutrient-enriched drainage from agricultural fields.

The restoration techniques employed can be readily transferred to other Florida estuaries with similar oyster habitat structure and non-viable oyster populations.

Oyster habitat design for this project replicated existing oyster habitat in Sarasota Bay. At both sites, the SBEP built five 75-foot diameter reefs utilizing fossil shell for the structural foundation. Each reef perimeter consists of a ring of oyster shell "sausages"— shell kept in biodegradable bags to prevent washout and dispersal.

The reef interiors consist of loose shell that provides multi-dimensional complexity. The fossil shell provides substrate for local oyster seed to attach onto and grow. The SBEP team monitors the reefs for oyster survival, growth and utilization by fish and invertebrates.

Volunteers contribute to every aspect of this project, helping to create the oyster "sausages" or bags of fossil oyster, transporting shell and unloading it onto the reefs and assisting with basic reef monitoring. The following community groups provided over 50 volunteers and dedicated 400 hours toward all phases of this project:

Volunteers contribute to every aspect of this project, helping to create the oyster "sausages" or bags of fossil oyster, transporting shell and unloading it onto the reefs and assisting with basic reef monitoring. The following community groups provided over 50 volunteers and dedicated 400 hours toward all phases of this project:

- SBEP Bay Guardians

- Sarasota Bay Parrot Head Club

- University of South Florida Environmental SustainaBULLs

- Friendship Volunteer Center's Retirees in Service to the Environment (RISE) Program

- Reef Innovations

This project is funded in part through a national partnership grant between the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration Community-Based Restoration Program and The Nature Conservancy.

The oyster habitat restoration project in Sarasota Bay and those in other coastal counties in Florida face several challenges. One significant challenge involves the permit process. To deploy material in Sarasota Bay, permits are required at the following levels:

- Federal: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- State: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- Local: Sarasota County Environmental Permitting

These agencies approved the Sarasota Bay projects; however, an exemption was required, as there is no standardized process for obtaining permits from all levels of government for sub-tidal habitat restoration. To address these permitting issues, partners held several strategy development workshops.

Another challenge is to ensure project sites are adequately marked and signage is properly installed. This is to prevent incidental navigation problems or accidents from boats travelling outside marked channels. The SBEP works with staff from both counties to install and maintain markers.

Another challenge is to ensure project sites are adequately marked and signage is properly installed. This is to prevent incidental navigation problems or accidents from boats travelling outside marked channels. The SBEP works with staff from both counties to install and maintain markers.

Site monitoring is a key component of restoration efforts. Moreover, monitoring newly-created oyster reefs is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of construction methods. Permitting and funding agencies often require such monitoring. For example, NOAA-funded projects must be monitored for two years. Currently, SBEP is monitoring the reefs at both project sites for oyster recruitment, growth and survival.

Habitat loss and degradation

High-quality habitats are critical for the health of marine and estuarine systems and the human economies that depend on them. Such habitats provide the following essentials for coastal and marine wildlife:

- Food

- Cover

- Migratory corridors

- Breeding/nursery areas

For humans, healthy coastal habitats attract tourism revenues and seafood industries that are vital to many local economies. These habitats also make coastal areas more resilient to storms and sea level rise. As coastal populations increase, coastal habitats are converted due to the following activities:

- Development

- Highway construction

- Diking

- Dredging

- Filling

- Bulk heading

- Other activities that degrade coastal ecosystems

When these natural resources are imperiled, so too are the livelihoods of those who live and work in estuarine watersheds.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

- Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Program

- Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program

- Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program

- Galveston Bay Estuary

- Mobile Bay Estuary Program

- Morro Bay National Estuary Program

- San Juan Bay Estuary Program

- Santa Monica Bay National Estuary Program

- Sarasota Bay Estuary Program

- Tillamook Estuaries Partnership

Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Program (APNEP)

Submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) is a critical resource for aquatic life because it:

- produces dissolved oxygen that fish need to survive;

- filters pollution; and

- serves as a food source, hiding place and home for fish, shellfish and crustaceans.

In fact, SAV is valued at about $12,000 per acre per year because of its importance to overall aquatic health and fisheries. In North Carolina, SAV plays an important role in the state's $1.75 billion fishing industry, which employs 24,000 people.

To help protect coastal environments and fishing industries in North Carolina and Virginia, APNEP led a state-federal effort that mapped 138,741 acres of SAV in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary, which spans southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. The map provides initial baseline information about the location, quantity and quality of underwater grasses along the coastline.

This information helps planners take steps to avoid development impacts on vulnerable, valuable SAV acreage. The baseline map also enables scientists for the first time to assess pollution level trends in North Carolina and Virginia coastal waters and evaluate coastal conservation efforts.

To map the SAV, airplanes with special cameras flew 1,795 miles along the estuarine coastline during a two-year period. Wind, waves, high humidity and sediment-laden water from rainfall sometimes interfered with the ability to photograph the SAV. So, volunteers sampled the water for clarity to ensure conditions were right for the high-altitude flights. Boat crews with underwater cameras also confirmed the accuracy of SAV locations.

The APNEP continues to work with state, federal, university and non-profit partners to establish an ongoing monitoring program through the North Carolina SAV Partnership.

For more information, see:

Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program (BTNEP)

Grand Isle is Louisiana’s biggest and only inhabited barrier island. The forests, back barrier marshes and sandy beaches of Grand Isle are considered one of the premiere birding destinations in North America. Restoration efforts in the area aim to restore and enhance bird habitat on the barrier island, which is part of the Mississippi Flyway.

For example, BTNEP partnered with The Nature Conservancy for an Arbor Day tree giveaway in Grand Isle. The team planted over 100 trees in the yards of homeowners.

The BTNEP also constructed a shade house at the Nicholls State University Farm to grow out woody species beneficial to Neotropical songbirds that utilize the Mississippi Flyway. The group collected seeds from trees around the state that are suitable for growing in coastal restoration sites with highly disturbed soils with high salinity and pH values. The team worked to establish these species on a man-made ridge in Fourchon and Grand Isle.

Through the multiyear Maritime Forest Ridge and Marsh Restoration Project, BTNEP and partner organizations seek to establish a chenier ridge and adjacent coastal marsh habitats just north of Port Fourchon. The project involved pumping earthen material via hydraulic dredge into shallow open water. The second leg of the project established a ridge with sloping sides and flanking marsh habitats. Volunteers worked to establish these sites by planting native herbaceous grasses and woody plants.

The unparalleled disappearance of Louisiana’s coast can only be surmounted by large-scale projects accomplished through partnerships that bring together the knowledge and resources necessary to address this overwhelming crisis.

Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program (CBBEP)

One of CBBEP's highest priorities is the protection and restoration of habitat for critical species. The CBBEP has an intensive focus on the purchase of major land parcels that provide increased high-quality acreage for waterbird nesting and shorebird habitat.

Galveston Bay Estuary Program (GBEP)

The GBEP’s habitat conservation partnership plans and executes expansive habitat restoration efforts. Since 2000, GBEP and partners have created, protected and enhanced over 20,585 acres of important coastal habitats, leveraging $78 million in local, industry, state and federal contributions. The GBEP operates its programs through a committee structure, and involves federal sources, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Coastal Impact Assistance Program, in its annual habitat conservation planning process.

Mobile Bay National Estuary Program (Mobile Bay NEP)

The Mobile Bay NEP (Alabama) partnered with the Baldwin County Commission to prevent on-site erosion and restore wetland, riparian and stream habitat in Magnolia Springs Park. The project was part of the Mobile Bay NEP’s Habitat Incentives Program, which promotes the acquisition and restoration of rare, highly sensitive or high-value sites within the Mobile Bay NEP study area.

Morro Bay National Estuary Program (Morro Bay NEP)

The Morro Bay NEP (located in California) and its partners improved fish passage in streams by removing man-made structures that impeded fish migration upstream. Their work resulted in enhanced access to 6.29 miles of stream for steelhead and other species. Additional habitat protection measures put in place by the program include land conservation purchases and easements.

San Juan Bay Estuary Program (SJBEP)

In 2008, the SJBEP (located in Puerto Rico) deployed 45 artificial reefs structures in the Condado Lagoon. The effort included the creation of the first underwater interpretative trail in the San Juan Bay Estuary and adjacent watersheds. The structures increased fish diversity by 90 percent. Moreover, approximately 2,500 new coral colonies are growing over the artificial reef surfaces. This project created and enhanced one acre of benthic habitat in the Condado Lagoon.

Santa Monica Bay National Estuary Program (SMBNEP)

In 2013, The Bay Foundation and partners completed the Malibu Lagoon Restoration and Enhancement Project, which restored an impaired wetland. This wetland was on U.S. EPA’s list of impaired water bodies for over a decade due to excess nutrients and low oxygen levels. The Project’s core goals included the following:

- Improving the ecological health of the lagoon’s system by enhancing habitats for native wildlife

- Creating several acres of new wetlands

- Increasing tidal flushing and water circulation to improve water quality and eliminate the “dead zones” and oxygen-deprived areas

Through two years of a five-year monitoring program, the project is on track to meet or exceed the documented criteria for success, with significantly improved water quality and circulation results, and improving condition scores over time. The Lagoon also now functions as nursery habitat for juvenile estuarine fish. Further, there is a shifting trend from a pre-restoration pollution-tolerant benthic invertebrate community to a more diverse, sensitive invertebrate community.

Another notable SMBNEP restoration effort is the Palos Verdes Kelp Forest Restoration Project. This project endeavors to offset the loss of 75 percent of giant kelp communities on the Palos Verdes Peninsula. In the past two years, community volunteers and commercial fishermen spent over 5,500 hours reducing sea urchin densities on the shallow rocky reefs and have restored 33 acres. The teams crushed 1.4 million sea urchins to enable the natural recruitment and regrowth of the giant kelp forest. Once completed, the project could encompass more than 150 acres.

The ecological response has been direct: giant kelp returned to the reefs and formed a canopy, and biomass and the richness of fish species increased. The remaining sea urchins, valuable to the red sea urchin fishery, are recovering quickly and are of value to the fishery, at a modeled benefit of 883 percent for every unit restored.

Sarasota Bay Estuary Program (SBEP)

Since 1993, SBEP (located in Florida) has overseen the completion of nearly 70 habitat restoration projects, with help from partner agencies, conservation groups and volunteers. Between 2014-15, the SBEP and several key partners managed two major wetland restoration projects.

The first project took place at Oscar Sherer Park, an urban state park in southern Sarasota County. This project consisted of the following three unique elements:

- Restoring the shoreline along Lake Osprey, which lies adjacent to the Park’s Nature Center and gets the concentration of Park visitors.

- Restoring an isolated wetland and creating new “frog ponds” adjacent to one of the Park’s hiking trails.

- Rehabilitating Big Lake, an historic borrow pit that needed extensive shoreline and shallow water work to restore habitat for wading birds.

The other major project took place at the FISH Preserve in the Village of Cortez, Manatee County. Acquired for its historically important coastal habitats, this 100-acre parcel saw a lot of abuse over the decades and needed a major restoration. Here, SBEP focused on restoring saltwater wetland and creating improved tidal circulation throughout half of the available upland acreage. The SBEP partnership planted extensive native vegetation along the wetland edges and upland islands.

The SBEP also completed two exciting subtidal habitat projects in the past few years.

In the first project, the SBEP created over four acres of oyster habitat. Completed over three years, the oyster reefs now support thriving fish and invertebrate communities. Moreover, they closely mimic the form and function of nearby natural oyster reefs.

In 2013, the SBEP rejuvenated its artificial reef program within Sarasota Bay and addressed nearly a dozen “bay reefs” that were idle since material was last placed on them in 2004. With the help of Reef Innovations of Sarasota, SBEP designed several new reef modules to attract juvenile gag grouper, which use the bay early in their life cycle.

Also in 2013, the project deployed several dozen modules, including “deep covers,” “Lincoln logs” and “layer cakes,” at three Sarasota County reefs. Subsequent monitoring revealed a variety of pelagic and reef fish, as well as highly economically valuable stone crabs, using these habitats.

The SBEP’s comprehensive study of the Bay’s artificial reefs found up to 30 different species of fish and invertebrates utilizing these structures as habitat.

Tillamook Estuaries Partnership (TEP)

The TEP facilitated 26 partner organizations in the Miami River Wetlands Enhancement project. The results of this 58-acre restoration initiative included:

- Creating 4,500 feet of new channels

- Placing 183 pieces of large woody debris

- Planting 19,000 native species

More than 51 acres were purchased by The Nature Conservancy and set aside as a protected reserve.

Nutrient loads

Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are necessary for plant and animal growth and support healthy aquatic ecosystems. In excess, however, nutrients can contribute to fish disease, red or brown tide, algae blooms and low dissolved oxygen. Sources of nutrients include point and non-point sources, such as the following:

- Sewage treatment plant discharges

- Stormwater runoff

- Faulty or leaking septic systems

- Sediment in urban runoff

- Animal wastes

- Atmospheric deposition originating from power plants or vehicles

- Groundwater discharges

When excess nutrients lead to low dissolved oxygen levels, marine animals must leave the low-oxygen zones for more oxygenated waters. Animals with limited mobility can die.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program (Buzzards Bay NEP)

Buzzards Bay NEP (located in Massachusetts) has succeeded in nitrogen-related water quality improvements. Two of their most important case studies are focused around the City of New Bedford and in the Wareham River estuary.

In New Bedford, wastewater facility upgrades and elimination of dry weather combined sewer overflow (CSO) discharges greatly improved water quality and promoted eelgrass recovery.

Buzzards Bay NEP advocated for a more stringent nitrogen discharge permit for the Wareham Wastewater facility in order to meet goals recommended in the NEP’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP). The effort succeeded, and resulted in the most stringent nitrogen discharge standard in Massachusetts (no more than 4 ppm Total Nitrogen from March to October).

Dramatic reductions in nitrogen concentrations in the Agawam River estuary and even the first signs of eelgrass recovery in the Wareham River estuary followed from the permit.

Long Island Sound Study (LISS)

Long Island Sound’s watershed is vast, with an area including most of Connecticut and portions of New York, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont. Nearly nine million people call this watershed their home.

With increased urbanization in the watershed, greater pollutant loads from sources such as sewage treatment plants and stormwater runoff have resulted in excessive nitrogen levels in the Sound. As a result, the Sound experienced increased algal blooms and decreased dissolved oxygen (DO) levels.

The Long Island Sound Study (LISS) worked to address the problem. Through years of research, monitoring and modeling, LISS helped identify nitrogen sources and the control levels necessary to improve DO levels and meet water quality standards. Moreover, LISS’ efforts led to the adoption of a target to reduce human sources of nitrogen to the Sound by 58.5 percent.

The LISS worked with state and local governments in Connecticut and New York to adopt a bi-state total maximum daily load (TMDL) and permitting scheme that incorporate the reduction target. The state agencies involved were the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (CTDEP) and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC).

The nitrogen TMDL recommends flexible, innovative implementation approaches. The CTDEP and NYSDEC applied such approaches to their point-source permitting programs, which are required under the Clean Water Act. Moreover, the CTDEP general permit scheme incorporates a nitrogen credit trading program. In the program’s first year, 39 plants reduced nitrogen output below their assigned permit limits, making them eligible to sell nitrogen credits valued at $2.76 million. The NYSDEC approach includes nitrogen load reallocation under bubble permits.

The innovative TMDL approach and permitting schemes are a model for how flexibility and market forces can achieve efficient waste load allocations. Stakeholders benefitted from the TMDL process through:

- increased cost savings;

- nitrogen reductions;

- improved water quality for recreation activities important to the regional economy;

- increased access to funding; and

- greater local, state and regional partnerships.

The TMDL established an enforceable 15-year schedule for point- and nonpoint-source nitrogen reduction. In 2010, the TMDL resulted in a reduction of 39,000 tons of nitrogen entering the Sound. The same year, the hypoxic area decreased from 180 to 169 square miles and the duration of the hypoxia event decreased from 79 to 45 days.

The TMDL is available at the Long Island Sound Study website. Exit

Peconic Estuary Program (PEP)

The PEP (located in New York) completed its system-wide nitrogen total maximum daily load (TMDL) in 2007 and is involved with implementing the TMDL. Current PEP initiatives include an overall nitrogen TMDL implementation assessment and other efforts aimed at nitrogen load assessment and reduction. For example, PEP provided funding to the Cornell Cooperative Extension’s Agricultural Stewardship Program for its Controlled Release Nitrogen Fertilizer pilot project to address nutrient pollution.

Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP)

Tampa Bay is Florida's largest open-water estuary, stretching 398 square miles at high tide. The Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) focuses on controlling nitrogen sources to restore vital underwater seagrass beds.

Seagrasses are an important barometer of the bay's health because they require relatively clean water to flourish. They also provide vital habitat for sportfish such as sea trout, snook and redfish. To develop an action plan for achieving nitrogen reduction goals, the Program set up the Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium. The Consortium is an innovative partnership consisting of more than 45 local governments, businesses and agencies. Since 1996, local communities working with the Consortium have implemented more than 250 projects, resulting in 400 tons of nitrogen reduced, to help meet nutrient loading targets.

In 1998, U.S. EPA approved a regulatory Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Tampa Bay. And, in 2007, EPA stated that all permitted nutrient sources within the Tampa Bay watershed must have an annual numeric limit or allocation for their nitrogen discharge to Tampa Bay.

Rather than relying on the regulatory agencies to develop allocated numeric limits, the Consortium developed voluntary nitrogen limits. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) and EPA participated in this effort throughout the process. Moreover, FDEP accepted the limits as meeting water quality requirements for Tampa Bay. Over a two-year period, Consortium members developed fair and equitable allocations for all 189 sources within the watershed.

Consortium members each contributed funds ($5,000 each) to support a technical contractor who helped them develop scientifically-sound options for allocations. Members realized that pooling their funds significantly reduced each member’s cost burden, since funding such work alone could cost an individual member more than $100,000. The TBEP facilitates the Consortium, manages the technical support contractor and collects funds from members.

Key benefits identified by Consortium members include the following:

- Allocations are equitable and based on sound science.

- The process and allocations were developed by Consortium participants and not by regulatory agencies alone.

- The collective process was cost-effective for all participants.

Efforts such as these have led to impressive progress toward Tampa Bay's long-term goal of recovering 12,350 acres of seagrasses bay-wide.

Tampa Bay gained 3,250 acres of seagrass between 2008 and 2010, an 11-percent increase that is the largest two-year expansion of seagrasses since scientists began regular surveys of this critical underwater habitat. The bay now supports more seagrasses than at any time measured since the 1950s.

Water in the bay now meets clarity goals and regulatory requirements, and seagrass has expanded by more than 8,000 acres since 1999.

Through the Southwest Florida Water Management District's Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) Program, scientists collect data on trends. They assess seagrass coverage in the bay approximately every two years, using a combination of maps produced from aerial photographs followed by ground-truthing to verify accuracy. Aerial photographs are taken in winter months when the water is clearer. All major bay segments show seagrass gains according to the SWIM data.

This includes the Old Tampa Bay segment in the northern part of the bay. This segment has been plagued by algae blooms and an expanding layer of thick, soupy muck near Safety Harbor in recent years. Seagrasses in Old Tampa Bay expanded by 858 acres, or nearly 15 percent, over 2008 levels. And, in Middle Tampa Bay, seagrasses increased by 1,549 acres, or 23 percent. Such increases could be a result of improving water quality overall.

Results from 2010 monitoring indicate that all bay segments met TBEP's adopted water clarity goals. Recent low-rainfall years, with less runoff entering the bay, may have contributed to the improvements. Gains also may be a function of constantly improving seagrass mapping techniques.

Despite the impressive gains, the bay is still 5,103 acres short of the target goal for seagrass set by TBEP and its local government partners. "Reaching that goal will require a continued commitment by the region to reducing excess nitrogen which remains the Bay's primary pollutant of concern", said Holly Greening, Executive Director of the Estuary Program.

Too much nitrogen fuels algae growth that turns the water cloudy and depletes oxygen.

"The seagrass increases are great news, especially as we mark the 20-year anniversary of the Estuary Program partnership this year," Greening said. "But we still need to manage nitrogen loadings, and to assess and address problem areas in the Bay."

Pathogens

Pathogens are disease-causing microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria and parasites that can create health risks for people enjoying recreation in and on the water. Pathogens can be introduced into estuaries from the following sources:

- Inadequately treated sewage

- Runoff from urban areas and animal operations

- Medical waste

- Boat and marina waste

- Combined sewer overflows

- Waste from pets and wildlife

Pathogens pose a health threat to swimmers, divers and seafood consumers.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

Mobile Bay National Estuary Program (Mobile Bay NEP)

Several Mobile Bay NEP (located in Alabama) efforts resulted in measurable decreases in bacteria concentrations.

The Big Creek Lake Watershed is the source of drinking water for most Mobile County residents. Here, Mobile Bay NEP supported outreach efforts and funding for projects to reduce bacterial loadings. The primary targets of the reduction efforts were a local dairy and property owners with failed septic tanks.

The Program supported technical assistance and community workshops conducted by the Mobile County Soil and Water Conservation District. These efforts resulted in pathogen loading reductions in Big Creek. The Program also assisted the Alabama Department of Environmental Management in the developing a TMDL for pathogens for Juniper Creek.

Additionally, a primary focus of the Program’s outreach activities is Three Mile Creek in the City of Mobile, which was since delisted for pathogen-related impairment. The Program will continue to play a primary role in the development and implementation of a watershed management plan for Three Mile Creek that results in restoration of the watershed’s hydrology.

Santa Monica Bay National Estuary Program (SMBNEP)

Population growth and uncontrolled development have had serious impacts on the water quality of Santa Monica Bay. For example, popular swimming beaches are often posted with warnings due to high pathogen levels. Also, significant amounts of trash and pet waste frequently wash from city streets into the bay during storm events.

The adverse impacts on water quality of pathogens from stormwater and urban runoff are well documented. The Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission conducted a landmark epidemiological study in 1995 that provided, for the first time, indisputable scientific evidence linking health risks to swimming in urban runoff-contaminated waters.

Finding solutions to water quality impairments caused by pathogens requires an understanding of the sources of pathogens and how these pollutants reach the bay and affect resources.

The sources of pathogens are numerous and disparate. Ultimately, however, they are a product of all the people, and their pets, that live in the bay's watershed. Moreover, pathogens reach the bay via numerous pathways, including the following:

- Runoff from lawns and streets into creeks and storm drains

- Municipal wastewater

- Commercial discharges

- Boating and shipping activities

Urban and stormwater runoff carried to the bay through the region's 5,000-mile storm drain network is a serious, year-round concern. In fact, each year sees an average of 30 billion gallons of runoff discharged through more than 200 outlets. Even in dry weather, 10 to 25 million gallons of water flow through storm drains into Santa Monica Bay every day.

And since the network was designed to convey flood waters to the ocean rapidly, all wet-weather flows and most dry-weather flows bypass wastewater treatment facilities and discharge directly to the bay. Reducing pathogen levels in the bay is a key goal of the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Plan, which emphasizes preventing pollution at the source and targeting specific areas for pollution reduction.

Stormwater and urban runoff are regulated through municipal, industrial and construction National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. Required under the Clean Water Act, the NPDES Stormwater Program is a comprehensive national program for addressing sources of stormwater discharges that adversely affect the quality of our waters.

The Program uses NPDES permits to require the implementation of measures to reduce the amounts of pathogens carried by stormwater runoff into local water bodies. Permit holders must develop and implement Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plans or Stormwater Management Programs using Best Management Practices (BMPs) to prevent the discharge of pollutants into the bay.

These efforts will improve the water quality of the bay to ensure that the waters are swimmable and fishable, the ultimate goal of the Clean Water Act.

Stormwater

Stormwater runoff is generated when precipitation from rain and snowmelt events moves across the landscape without percolating into the ground. As the runoff flows over the land or impervious surfaces (e.g., paved streets, parking lots and building rooftops), it can accumulate:

- debris;

- chemicals;

- sediment; and

- other pollutants.

If the runoff is untreated, it can degrade water quality.

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

- Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program

- Casco Bay Estuary Partnership

- Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program

- Delaware Center for the Inland Bays Estuary Program

- Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership

- Morro Bay National Estuary Program

- Puget Sound Partnership

Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program (Buzzards Bay NEP)

The Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program (located in Massachusetts) assists communities in meeting their stormwater challenges.

In one initiative, the Program provided summer jobs to students interested in GIS mapping techniques. The students surveyed roadways and shorelines in the Buzzards Bay study area to map the stormwater infrastructure. Fire departments received this information to help them respond to hazardous material spills. The map data also were used to create an Atlas of Stormwater Discharges in the Buzzards Bay Watershed.

The atlas and companion CD include maps of more than 2,600 stormwater discharges and more than 12,000 catch basins in Buzzards Bay. The Program distributed these materials to municipal boards and local libraries. Moreover, boards receiving the document and poster-sized maps included the following:

- boards of selectmen

- departments of public works

- boards of health

- conservation commissions

The Program also developed "Unified" regulations to ensure consistency among planning boards, conservation commissions and boards of health in addressing stormwater issues.

The principle behind these regulations is that no new construction should create any new direct untreated stormwater discharges that degrade water quality or living resources, and that stormwater must be treated on site. A rainfall of 1-1/4 inches or greater occurs in the Buzzards Bay area, on average, every four months.

The Program adopted the standard of treating the first 1-1/4 inch rainfall on impervious surfaces within a watershed. This rule captures, on average, 90 percent of the rainfall volume that falls in a given year. The Program also offers technical assistance in implementing these stormwater regulations.

Casco Bay Estuary Partnership (CBEP)

The CBEP (located in Maine) works to advance an innovative strategy to clean up stormwater pollution in areas developed before widespread use of effective stormwater management techniques.

Long Creek is an urban stream near Portland, Maine, with a variety of water quality problems. The Long Creek watershed is home to one of the largest retail and commercial centers in Maine (the Maine Mall). Nearly one-third of the watershed is covered with impervious surfaces such as:

- roads

- parking lots

- rooftops

The Maine Department of Environmental Protection identified stormwater runoff as the source of the water quality problems, and the Conservation Law Foundation threatened legal action if these problems were not addressed. Business and land owners in the watershed faced new legal obligations to clean up the creek, which could have run to $10,000 per impervious acre per year.

The CBEP played a central role in parlaying those new legal obligations into a voluntary, community-based and collaborative approach to the restoration of Long Creek. At the heart of the program is a sustainable funding mechanism through which private property owners address their permit obligations by collectively financing stormwater management throughout the watershed.

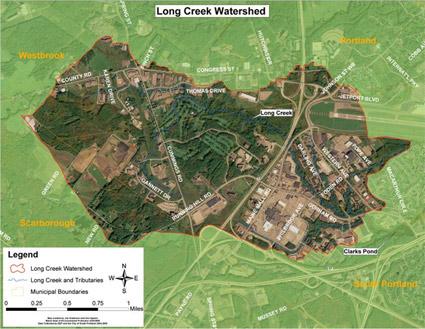

The 2000+ acre Long Creek Watershed, with the Maine Mall and associated commercial development to the lower right.The Casco Bay NEP was instrumental in getting landowners to work together rather than separately. The collective approach, based on a 10-year, $14 million watershed restoration plan, allowed participants to:

The 2000+ acre Long Creek Watershed, with the Maine Mall and associated commercial development to the lower right.The Casco Bay NEP was instrumental in getting landowners to work together rather than separately. The collective approach, based on a 10-year, $14 million watershed restoration plan, allowed participants to:

- target the most cost-effective projects first;

- defer less valuable projects;

- benefit from economies of scale; and

- qualify for low-interest State Revolving Fund (SRF) loans.

With this approach, costs to landowners dropped by about two thirds.

The Long Creek Watershed Management District (LCWMD) consists of owners of more than 115 properties in the watershed who signed the "Participating Landowner Agreement." This demonstrates that a collaborative approach to stormwater management can be attractive to the business community.

Further, LCWMD installed more than $2 million worth of water quality improvement structures. An accelerated construction schedule was made possible by State Revolving Fund loans, to be repaid over 20 years by fees paid by participating landowners.

Efforts also included constructing a stormwater best management practice (BMP) maintenance and inspection database. The database assists LCWMD staff and landowners with upkeep.

Street sweeping and catch basin cleanouts in the Long Creek watershed in one year alone reduced sediment delivery to surface waters by many tens of tons. Improved stormwater control devices installed at several locations in the watershed further increase sediment capture. Information on BMPs for landscape and winter maintenance helps reduce soil erosion and limit overuse of salt and sand in the winter, further reducing delivery of sediment to the Creek.

The CBEP supports efforts in Long Creek in a variety of ways, including:

- loaning water quality monitoring equipment;

- providing meeting space for LCWMD-related meetings; and

- facilitating collaboration between LCWMD and area scientists.

Additionally, CBEP recently provided funding to analyze water samples collected in Long Creek to determine nitrogen concentrations.

The Long Creek water quality monitoring program is the most comprehensive urban watershed monitoring effort in Maine, and is among the most sophisticated in New England. Landowners appreciate both the efficiency and quality of the program, while enjoying significant economies of scale.

Delaware Center for the Inland Bays (CIB) Estuary Program

The CIB and partners constructed wet-swale bioretention areas and a series of infiltration pits along South Pennsylvania Avenue. These retrofits are estimated to have reduced 48 lbs. of nitrogen and 7 lbs. of phosphorus to date.

Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program (CHNEP)

Throughout the CHNEP watershed (located in Florida), partners have implemented a variety of effective urban stormwater management projects:

- The Southwest FL Regional Planning Council hosted a Managing Wet Weather with Green Infrastructure Workshop in 2009.

- The South FL Water Management District adopted updated stormwater regulations.

- The City of Fort Myers improved stormwater management, filtration and habitat along Billy's Creek and in its downtown redevelopment.

- The City of Punta Gorda incorporated improved stormwater treatment during its recovery from Hurricane Charlie.

- The Cities of Bonita Springs and Fort Myers beach included extensive filter marches with recent roadway improvement projects, including additional catch basins.

- The City of Sanibel conducted hydrologic restoration along the Sanibel River, acquired conservation lands, and combined their Water Resources Divisions of stormwater, wastewater and water supply, resulting in a project that uses vacated spray fields for stormwater treatment.

Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership

The Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership (located in Oregon) is engaged in various efforts to reduce stormwater run-off.

For example, the Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership secured grants to initiate Schoolyard Stormwater Projects at five schools. Three of the projects are complete.

The Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership engaged corporate partners to design stormwater facilities and outdoor classrooms, and coordinated all permitting and construction. The projects engaged students and contractors in project construction and ongoing maintenance activities. Moreover, the projects integrated multiple stormwater focused class visits and field trips with service learning projects in each school’s schoolyard.

In 2003, the Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership developed a web-based field guide to highlight local examples of effective, innovative stormwater management techniques. The web pages include local examples, with methods and contact info, as well as 24 stormwater management technique fact sheets developed by the City of Portland.

Additionally, the Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership provided stormwater management assistance to help two communities meet federal Phase II stormwater requirements.

Morro Bay National Estuary Program (Morro Bay NEP)

The Morro Bay NEP played a primary role in funding two “how-to” guides for local residents: a Low Impact Development (LID) guide and a greywater construction and use guide. Part of an ongoing series, these guides explain how to install rainwater gardens, greywater systems and other LID practices. In addition, Morro Bay NEP provided funding to bring guest speakers to the area to discuss water conservation and rainwater harvesting.

The National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) guidelines under the Clean Water Act mandate the City of Morro Bay to manage non-point source pollution entering Morro Bay through the storm drain system. To help implement the management program, the Morro Bay NEP partially funded the creation of a Morro Bay GIS storm drain atlas. The Morro Bay NEP also is working with the City of Morro Bay to update their TMDL Wasteload Allocation Attainment Plan, which:

- identifies the sources of bacteria;

- lays out best management practices (BMPs) to address them; and

- describes monitoring efforts to track their success.

Morro Bay NEP staff consulted with the city’s effort to create an interpretive sign covering marine debris and runoff that is focused on tourists and residents. Two of the signs were installed in late 2010.

In 2007, the program teamed up with the City of Morro Bay and a local Eagle Scout candidate to mark more than 300 storm drains with "no dumping" plaques.

Further, the Morro Bay NEP worked with the City of Morro Bay, Los Osos Community Services District, and County of San Luis Obispo to help them implement the education and outreach components of the Stormwater Management Plans. Here, the Morro Bay NEP assisted by:

- consulting on the efforts;

- funding projects through its grants program; and

- participating in the county's Central Coast Partners for Water Quality.

Additionally, the Morro Bay NEP funds an annual newspaper ad and television PSA campaign. The campaign’s message is that big improvements in water quality can come from small changes in behavior, such as the following:

- icking up after pets

- Avoiding over fertilizing lawns and residential landscaping

- Repairing automotive oil leaks

Puget Sound Partnership

Innovative Stormwater Management: Transitioning the Region to LID

Stormwater runoff causes many serious problems in Puget Sound – in fact, it may be the most serious undermanaged threat to the health and vitality of the sound.

Studies show that the source of many toxic chemicals found in the sound are delivered via surface runoff. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) researchers document very high mortality rates of salmon within hours of entering urban streams — due to stormwater runoff.

More and more of the sound's productive shellfish rearing and harvest areas are closed due to stormwater runoff. High stormwater flows cause flooding and damage fish and wildlife habitat, contributing to iconic salmon species being threatened with extinction.

The Puget Sound NEP (Puget Sound Partnership) recognizes the limitations of conventional stormwater management techniques in protecting water resources from the many effects of stormwater runoff. That is why the partnership and its predecessors have worked with regional partners since 2000 to transition the region to the use of low impact development (LID) practices. And it is happening. Today, the Puget Sound region is a hotbed of LID activity.

Toxics

If consumed by humans, organisms exposed to certain toxics can pose a risk to human health. Wildlife and aquatic plants and animals can be harmed by consuming contaminated fish and water.

The following are common toxics that threaten estuaries:

- Metals, such as mercury

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

- Pesticides

Ways that such toxics can enter waterways include:

- Storm drains

- Industrial discharges

- Runoff from lawns, streets and farmlands

- Discharges from sewage treatment plants

- Atmospheric deposition

NEP Approach/Success Stories

In this section:

New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program

In 2001, the Harbor & Estuary Program’s Toxics Work Group initiated a polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) monitoring project in partnership with the Linden Roselle Sewage Authority. In 2012, water quality managers identified a significant source of PCBs and remediated the site polluted by those toxic compounds.

San Juan Bay Estuary Program (SJBEP)

San Juan Bay Estuary Program (located in Puerto Rico) conducted a toxics recovery project Condado Lagoon, which had become a giant cesspool due to high concentrations of fecal coliform. Here, SJBEP worked with partners to eradicate the sewage discharge and improve water quality.

In 2009, the last large-scale infrastructure work done in the area eliminated a sanitary water pump station with a long history of sewage bypass.

San Francisco Estuary Partnership (SFEP)

Outdoor insecticide applications—commonly used in California to control ants—have been directly linked to toxicity in California creeks. In 1998, all urban creeks in the San Francisco Bay Area were added to the Clean Water Act Section 303(d) list due to known or suspected impairment from the pesticide diazinon. Since 2004, diazinon is no longer available for purchase, and applicators are using other pesticides such as pyrethroids instead.

Indoor pesticide applications also are linked to water pollution due to clean up and application methods. That is, when pesticides wash down drains, they pass through water treatment plants that are not designed to remove these substances and can reach water bodies.

The SFEP's Urban Pesticide Pollution Prevention (UP3) Project works to prevent water pollution from urban pesticide use. The UP3 Project tracks, analyzes and shares information about:

- Urban pesticide use.

- Regulatory processes related to pesticides of concern.

- Science and monitoring data on pesticides.

The UP3 Project supports the Urban Pesticides Committee, which for more than a decade has provided a forum for stakeholders to coordinate and develop ways to reduce pesticide impacts on aquatic life. The UP3 Project also provides tools to help municipalities reduce their pesticide use. This Project works to reduce this toxicity in creeks in three main ways:

- Providing tools to municipalities to reduce municipal pesticide use and to conduct outreach to their communities on less-toxic methods of pest control (e.g., baits, caulking and improved sanitation);

- Compiling the latest relevant scientific information and providing regular e-mail updates and informative annual reports;

- Providing technical assistance to California Water Boards and municipalities to promote the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) and the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) support for preventing water quality problems from pesticides.

Specifically, the SFEP UP3 has:

- Established the UP3 web site, which is cited by researchers, water quality managers and regulators as a key resource for their work;

- Trained hundreds of municipal staff and pest managers on the links between pesticide use and water quality and how to manage ant problems using integrated pest management;

- Completed the only available analysis of urban pesticide use patterns (PDF)(14 pp, 231 K, About PDF) Exitto inform water quality and pesticide agency responses to pesticide-related surface water toxicity.

For more information, see: Urban Pesticide Pollution Prevention (UP3) Project Exit

Additionally, the SFEP collaborated with the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) to conduct annual water quality monitoring and water quality trends analysis in the San Francisco Bay. These partners develop protocols for surface water quality monitoring, such as its toxicity identification evaluation (TIE) procedures for pyrethroid-caused toxicity that are now routinely used in toxicity testing laboratories throughout California.